Erecting the Pillars of Anaesthesia- Bringing Pain Free Surgery Into Reality

By Fawaz Prem Navaz, Zheng Cheng Zhu

Key reference:

Robinson D, Toledo A. Historical development of modern anesthesia. Journal of Investigative Surgery. 2012 May 14;25(3):141–9. doi:10.3109/08941939.2012.690328

Quick Summary

-

From having to perform surgery on an awake patient to now being able to safely operate on a sedated patient, advancements in anaesthesia have revolutionised intra-operative and post-operative care

-

William T.G.Morton successfully administered the first ever general anaesthesia on October 16th, 1846

-

First use of endotracheal intubation for anaesthesia is attributed to Sir William Macewen in 1878

-

Carl Koller investigated Cocaine as the first topical/ local anaesthetic agent in 1884

-

Chevalier Jackson introduced his Jackson laryngoscope in 1913

-

The Australian Society of Anaesthesia (ASA) is formed on January 19th, 1934, guiding the way for recognition, advocacy and support for anaesthetists as medical specialists in Australia

-

Sir Robert Reynolds Macintosh introduced the well known Macintosh blade in 1943

-

Harold R. Griffith and G. Enid Johnson introduced the first ever neuromuscular blockade agent, Intocostrin (Curare) in 1942

-

Concept of Minimum Alveolar Concentration (MAC) introduced by Seymore S. Kety in 1965

-

Introduction of Propofol and total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) in 1977

-

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) founded in 1992

Preamble

It is a cold and gloomy Saturday in 1840. You wake up, drenched in a feverish sweat. The cause? An annoyingly painful infected tooth. You had planned to enjoy your well-earned Saturday off, sipping on your deliciously warm coffee and breakfast in the cosy comfort of your home. Unfortunately, you are condemned to a trip, through the miserable winter Melbourne rain, to the dentist instead…Luckily, you don’t go far before you see a new dental clinic that had just recently opened down the street. In it, your saviour/ tormenter awaits – an extremely skilled dental veteran. They take one look at you and usher you directly into the dental chair, skipping the waitlist, as the situation seems dire. This infected tooth seems to have festered into a tooth abscess. The dentist informs you that despite their experience, this procedure was going to be a long one- and not only that- it was going to be extremely painful.

“What choice do I have?”

You accept your fate and settle into the chair. The dentist begins their work, but despite their best efforts, your screams of agony and pain are heard across the town, so much so that the pastor passing by stops to see if they could be of any help in what they assumed to be an exorcism…

The above scenario, although sounding far-fetched, was a common experience for many that underwent any form of surgery prior to the 1840s, with some hospitals at the time even reporting an alarmingly high surgical mortality of over 50%.

Achieving a state of amnesia, providing adequate analgesia and utilising muscle relaxation, which form the pillars of what we know today as the Anaesthetic Triad, were unheard of for many surgeons and patients alike in the past.

Have you ever stopped to think about how anaesthesia which we take for granted today was discovered and came about? In this article we take a trip down memory lane to celebrate the visionaries whose intelligent curiosity and hard work gave rise to these wondrous discoveries and inventions, guiding us to a place where surgery can be performed and undertaken in a safe and ethical manner.

Inhaled Anaesthetics

October 16th marks on the calendar “World Anaesthesia Day”- but have you ever wondered why? On this very same day in 1846, a young dentist by the name of William T.G. Morton successfully demonstrated the first ever surgical procedure performed under general anaesthesia using a gas known as Diethyl Ether. The minor procedure performed by surgeon John Collins Warren at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston sent shockwaves across the medical world, as at the time it was the first operation in which the patient was unconscious for its entire duration and reported no recollection of the pain afterwards. For this, the Massachusetts General Hospital amphitheatre, where the procedure was completed, was coined as “The Ether Dome”, and Dr. Morton, would later be given the title “Founder of Modern Anaesthesia”.

Despite its publicity, ether was in fact not the first inhaled anaesthetic ever used- that title is given to nitrous oxide. This discovery was made by another dentist, and colleague of Dr. Morton’s, Horace Wells in 1844. During his time at an “Ether Frolic” (a fancy dinner party where the rich go to enjoy and experience the pleasures of inhaling nitrous), Dr. Wells noticed that those in an ‘elevated’ state post-inhalation did not register any pain when they bumped into things. This led him to trial nitrous oxide in his practice, however unlike Dr. Morton, Dr. Wells did not achieve the same level of fame and success due to a failed public demonstration using his anaesthetic drug of choice.

Although ether had revolutionised surgery in the Victorian era, it wasn’t without its disadvantages. These included high flammability, prolonged induction time, a high incidence of nausea and vomiting, and a very unpleasant and persistent odour. Due to this, chloroform was also used as an anaesthetic from 1847. A physician by the name of Sir James Young Simpson used chloroform as his drug of choice to shield pregnant women from the pains of childbirth and labour. It was considered by many to be superior to Ether due to its increased potency and faster onset of action, meaning that less of it had to be used, leading to a reduction in cost. It was therefore considered more portable as the physician had to bring less with them. It also had the added benefit of not requiring any special inhaler/ instrument as a simple handkerchief or sponge would do the trick. Lastly, patients often preferred chloroform over ether as the sensations were far more pleasant.

Despite the myriad of benefits, chloroform’s reign was short-lived in the most tragic fashion. Hannah Greener, an otherwise healthy 15 year old girl, would become the first recorded death under anaesthesia on 28th January 1848, a meagre one year after chloroform was first utilised. To this date, academics have debated the cause of Ms. Greener’s death: was it a fatal ventricular arrhythmia triggered by chloroform, or was it hypoxaemic arrest secondary to respiratory depression and subsequent aspiration of the water and brandy that was poured by her physician into her mouth to “resuscitate” her? Nevertheless, Ms. Greener, through what was supposed to be a routine toenail removal, became a “first” no one wanted. She served as a stern reminder of the dangerous, sometimes lethal, nature of the anaesthetic drugs we use, and the utmost care that needs to be demonstrated to ensure that patients are kept safe. Unsurprisingly, the case of Hannah Greener caused widespread concern amongst the medical community resulting in chloroform’s use waning considerably.

It would be almost a century till the next discovery came in the 1930’s when it was noted by researchers that halogenation of a parent hydrocarbon significantly reduced its flammability. John C Krants Jr used this principle to synthesise fluroxene by halogenating the flammable agent Vinamar (Ethyl Vinyl Ether). Its use, although prevalent, was short-lived as there were many reports of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Charles Suckling’s creation from 1954, halothane, garnered worldwide success due to its more pleasant odour, higher potency, low flammability, and low toxicity. However, its safety was called into question when instances of hepatic necrosis and failure were reported post halothane anaesthesia in patients where this liver failure was not a previous risk. Following this, although the National Halothane Study of 1964 showed that the incidence of liver failure was no different with any anaesthetic used, the damage was already done and the idea of “halothane hepatitis” perpetuated the stigma around its use resulting in its eventual decline.

Concurrently, the salient concept of the Minimum Alveolar Concentration (MAC) was proposed by Seymore S. Kety in 1965, allowing researchers and physicians to objectively measure the amount of anaesthesia a patient was receiving from an inhaled agent.

Enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane were all subsequently developed with sevoflurane now being used extensively due to its lack of complications, fast recovery time and resultant earlier discharge.

Intravenous Anaesthetics

The question of “which of inhaled or intravenous (IV) anaesthesia is better”, is one that always gets the anaesthetic tea room in a ruckus. The cause of this commotion can be attributed to the work of Pierre-Cyprien Ore’. Although his work never gained much popularity, his successful attempt at IV anaesthesia using chloral hydrate in 1872 opened the door to research into IV agents. A concoction of IV morphine and scopolamine, colloquially known as “Twilight Sleep”, gained popularity throughout the WW1 era (especially in obstetric anaesthesia), however was also short-lived due to reports of serious side effects in some patients.

It wasn’t until 1932 when Dr. John Lundy added wind to the sails of IV agents with his introduction of sodium thiopental and barbiturates as IV induction agents. Nineteen forty-four saw the first issues with sodium thiopental, as its profound cardiac depressant effect came to light, resulting in frequent and sudden deaths. The 1950s saw the rise in use of phencyclidine, however its use was once again short lived due to its behavioural and cognitive adverse effects. In today’s age, it is commonly used for recreational purposes.

Nineteen sixty-two saw the advent of ketamine, which is still used for sedation and analgesia to this day. It also had the added benefit of being the only induction agent that can be administered via both IV and intramuscular routes. Despite these benefits, the postoperative hallucinations experienced by some patients lead clinicians to turn to other drugs as their main induction agent of choice. Etomidate, the ultra-short acting, non-barbiturate hypnotic of 1973 saw an increase in popularity as even at higher doses it had very minimal cardiovascular suppression and seemed to be tolerated well. The only serious side effect noted was myoclonus in some patients during induction.

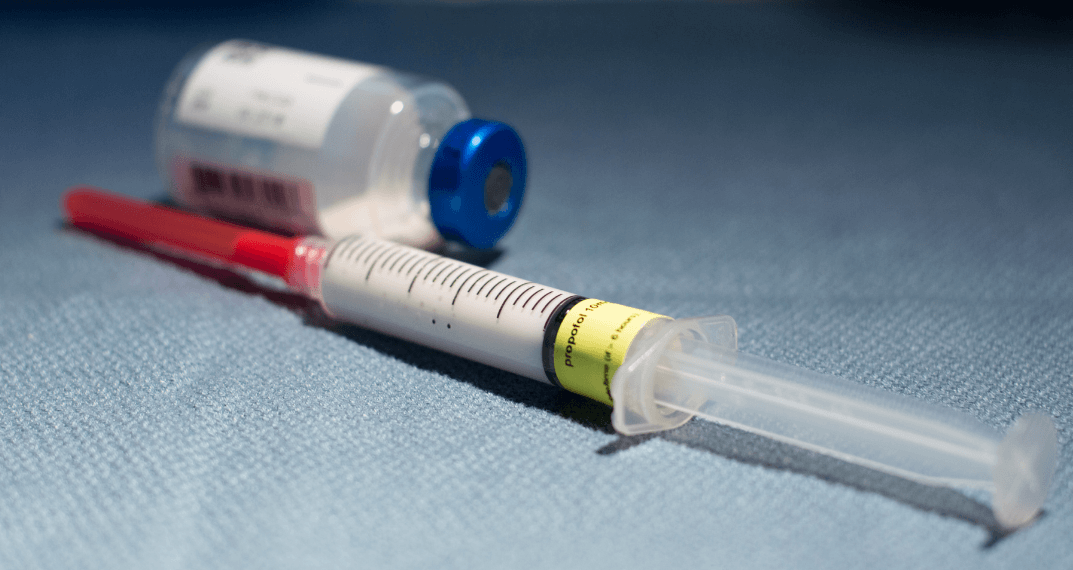

Nineteen seventy-seven brought forth the introduction of propofol and the birth of the revolutionary new method of general anaesthesia, “TIVA” (Total In-Travenous Anesthesia). A few of the many benefits noted included significantly greater suppression of laryngeal reflexes and anti-emetic properties, resulting in substantially shorter recovery times. The ability to utilise TIVA proved very useful especially in cases where any and all volatile gases need to be avoided, such as in patients with a history of malignant hyperthermia.

Neuromuscular Blockade

Despite the advancements in anaesthesia and sedation, surgeons had to fight a losing battle against their patients’ bodies and musculature for nearly one hundred years without the use of muscle relaxation. Although muscle relaxation could be achieved with the agents available at the time, drastic increases in doses were required to achieve adequate muscle relaxation leading to issues for patients due to the wide spectrum of tolerances to anaesthetic.

The work of Harold R. Griffith and G. Enid Johnson was the saving grace surgeons needed. Their introduction of Intocostrin (curare) into their clinical practice in 1942 significantly reduced the amount of anaesthetic required, increased the volume of surgery, improved working conditions for the surgeon and reduced morbidity and mortality.

From that time, several additional agents have been developed and synthesised however many of them possessed unfavourable side effects, largely autonomic, and hence were soon abandoned. Aminosteroid-based agents such as pancuronium (1966), vecuronium (1980), and rocuronium (1991), have become more mainstream as they maintained a positive safety record.

Use of Endotracheal Tube Intubation

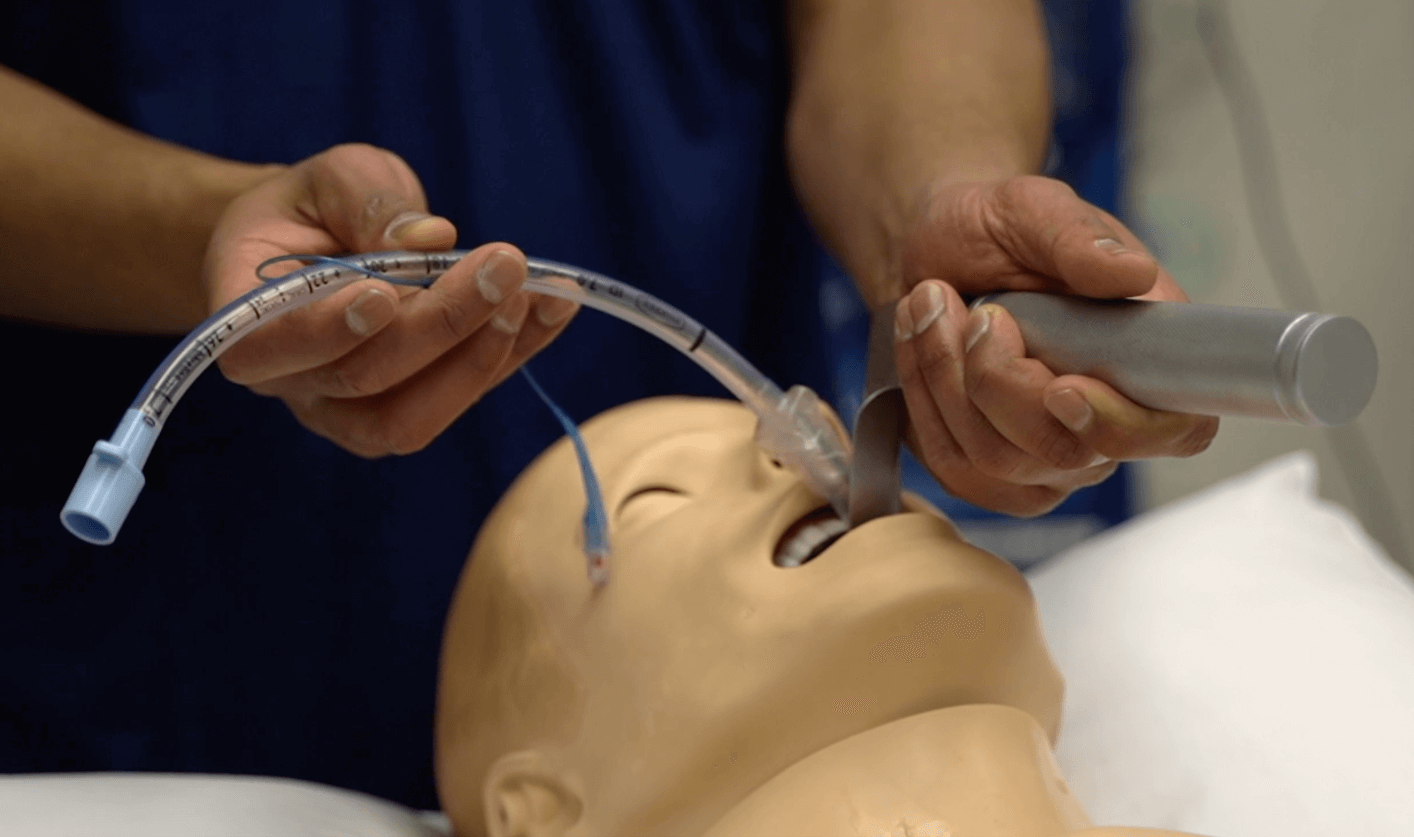

With the rapid advancements in the field of anaesthesia, there was also a simultaneously increasing demand for adjuncts, and with induction and sedation agents becoming more effective, the need to quickly secure a patent airway was of utmost importance. Interestingly, the first reports of endotracheal intubation was not for administering anaesthesia, but rather, for maintaining a patent airway in children with diphtheria. A paediatrician by the name of Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer (1841–1898), passed the metal “O’Dwyer” tube into the trachea blindly to help support and manage his young patients.

The first use of endotracheal tube (ETT) for anaesthesia is attributed to Sir William Macewen, who, in 1878, utilised this method for operations of the mouth, primarily to combat oedema of the epiglottis and to prevent blood from entering the larynx, hence protecting his patients from aspiration. The development of the mineralized-rubber endotracheal tube by Ivan W. Magill and Edgar S. Row-Botham provided a safer and more tailored fit in the airway, allowing for both inspiration and expiration during surgery. Arthur Guedel and Ralph M. Waters’ addition of a cuff, further improved on previous designs, allowing for positive pressure ventilation, the potential for one lung ventilation, and the decreased incidence of pneumothoraces with thoracic surgeries.

Fast-forwarding to more modern times, Peter Murphy’s ingenious utilisation of the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope in 1967 revolutionised tracheal intubation allowing for much safer outcomes in patients that are at higher risk due to having more difficult airways.

Introduction of Laryngoscopes

Initially, techniques used to intubate included blind or tactile methods, as the only way to visualise the larynx was via indirect laryngoscopy, which involved utilising small mirrors at the end of instruments to visualise the larynx. The increased use of muscle relaxants in the 1940s necessitated the ability of anaesthetists to establish an airway rapidly with better visualisation of the larynx. Hence, the primitive laryngoscope was born.

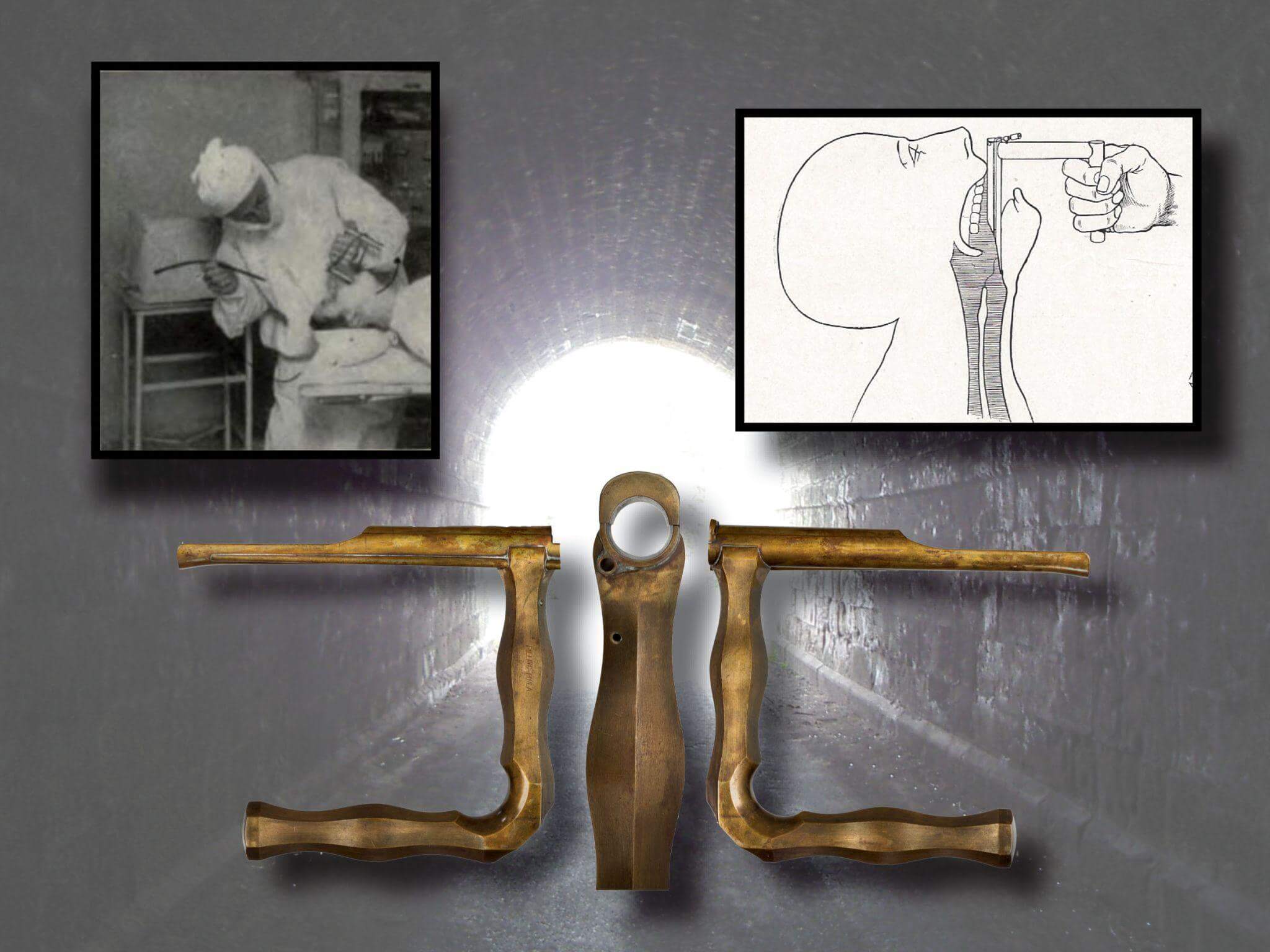

Chevalier Jackson’s Laryngoscope introduced in 1913

Chevalier Jackson fashioned a U shaped blade in 1913 (shaped much like a Sim’s speculum) with no curve at the tip and coined it the Jackson laryngoscope. He later added a light at the end for better visualisation.

The 1940’s saw the introduction of iterations of the laryngoscopes more similar to those used today. Robert A Miller’s creation of 1941, the Miller blade, was one where the blade had a slight curve at the end enabling easier retraction, and visualisation, of the epiglottis.

The Mac blade that is revered by many anaesthetists, came from Sir Robert Reynolds Macintosh’s work in 1943. He was the first to describe that placing the tip of the laryngoscope in the epiglottic vallecula, allowed for much better visualisation and exposure of the entire larynx when lifted. He also argued that lifting the epiglottis the traditional way stimulated the superior laryngeal nerve, increasing the risk of bradycardia and stimulation of laryngeal reflexes. Hence, the use of his shorter, curved blade proved easier and safer as it required less sedation and reduced the incidence of laryngospasm.

Regional and Local Anaesthesia

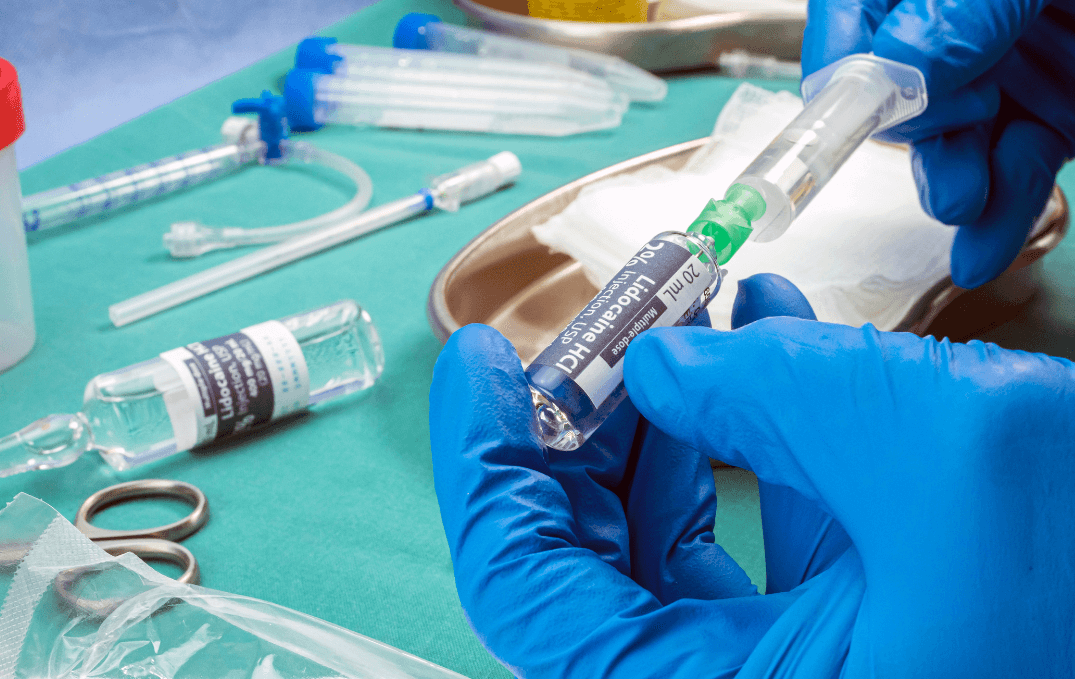

Have you ever wondered why many local anaesthetic agents end in “-caine”? The answer interestingly is because cocaine was the initial parent agent to many of the local anaesthetics used today. A collaboration in 1884 between Carl Koller, an Austrian ophthalmologist, and Sigmund Freud, the Father of Psychology, first saw the investigation into cocaine for its topical/ local anaesthetic properties. Due to the lack of agents available to topically anaesthetise the eye, Dr. Koller trialled cocaine and found it to be effective.

Later in the same year, Alfred Hall and William Halsted’s investigation into how cocaine acts when injected under the skin and around nerves, resulted in them achieving local and ulnar nerve blockade, giving rise to regional anaesthesia.

Moving forward, August Beir successfully achieved spinal anaesthesia in 1898, revolutionising regional and axial anaesthesia.

Although cocaine proved to be revolutionary, its toxicity and addictive potential proved to be problematic with even Alfred Hall and William Halsted falling victim to its addictive properties. These concerns encouraged further research into local anaesthesia resulting in the commercialisation of amylocaine by Ernest Fourneau, and novocaine by Alfred Einhorn in 1904.

Another advancement in regional/ local anaesthesia came in 1913 when James Tayloe Gwathmey aimed to relieve birth pains utilising a mixture of ether and oil administered rectally. The introduction of rectal anaesthesia avoided systemic issues on the mother and foetus associated with inhaled agents.

Anaesthesia in Australia

Prior to the 1930’s, Australia lacked any structured anaesthetic accreditation and training organisations. This gap in the Australian healthcare system was resolved with the formation of the Australian Society of Anaesthetists (ASA) on January 19th, 1934. The 7 founding members of the 4th Australian medical organisation aimed to improve the status and recognition of anaesthesia as a specialty, support the exchange of ideas and information between anaesthetists in Australia and those overseas, and encourage research into anaesthesia and hence, publish papers in anaesthesia. These goals formed the backbone of the ASA that are upheld till this day.

Nineteen fifty-two saw the ASA setting up a faculty within the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) to train specialist anaesthetists. In 1992, this faculty separated into its own college known as the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA). Following on from this, the Faculty of Pain Medicine was formed within ANZCA in 1998.

Parting words

Today, there are more than 7100 anaesthetists across Australia and New Zealand, their work made only possible by the pioneers who sought to improve the lives of those undergoing surgery. Just like the eras before us, modern day anaesthesia faces unprecedented challenges: with an ever ageing and comorbid patient population undergoing more sophisticated and audacious surgical interventions, anaesthesia has needed to branch out of the comfort of the operating theatre to the forefront of multidisciplinary perioperative medicine to optimise our patients’ operative journey. Beyond the clinical realm, anaesthesia will continue to focus upon its environmental responsibilities as the most frequent prescribers of potent greenhouse gases and producers of plastic waste. As we emerge from the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, we realise that the anaesthesia workforce is not immune to the physical and psychological toll, and workforce shortages will continue to dominate policy decisions as more and more anaesthetists are needed for our growing communities, especially outside of the cities. All these will continue alongside our quest to answer the same old question our trailblazers sought to answer 180 years ago: how can we give the safest and most effective anaesthesia for our patients. We look forward to the advances and achievements our generation of anaesthetists will bestow upon our great specialty.

References

Robinson D, Toledo A. Historical development of modern anesthesia. Journal of Investigative Surgery. 2012 May 14;25(3):141–9. doi:10.3109/08941939.2012.690328

Gazdić V. A brief history of anaesthesia. Scripta Medica. 2020 Oct 9;51(3):190–7. doi:10.5937/scriptamed51-25992

Nou S. Ep90. All things 90! [Internet]. Australian Anaesthesia- ASA Podcasts by Dr Suzi Nou. 2024. Available from: https://asa.org.au/asa-public-podcasts/

Aranake A, Mashour GA, Avidan MS. Minimum alveolar concentration: Ongoing relevance and Clinical Utility. Anaesthesia. 2013 Feb 16;68(5):512–22. doi:10.1111/anae.12168

PCP fast facts [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 9]. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs4/4440/index.htm#:~:text=Department%20of%20Justice.-,What%20is%20PCP%3F,altering%2C%20hallucinogenic%20effects%20it%20produces

Williams LM, Boyd KL, Fitzgerald BM. Etomidate [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 9]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535364/#:~:text=Indications-,Etomidate%20is%20an%20ultrashort%2Dacting%2C%20non%2Dbarbiturate%20hypnotic%20intravenous,administered%20only%20by%20intravenous%20route

Raghavendra T. Neuromuscular blocking drugs: Discovery and development. JRSM. 2002 Jul 1;95(7):363–7. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.7.363

Gifford RRM. The o’dwyer tube. Clinical Pediatrics. 1970 Mar;9(3):179–85. doi:10.1177/000992287000900313

Chevalier Jackson’s Laryngoscope: Seeing Light at the End of the Tunnel. Anesthesiology [Internet]. 2021 May 11 [cited 2024 Apr 9];134(6):936–6. Available from: https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article/134/6/936/115712/Chevalier-Jackson-s-Laryngoscope-Seeing-Light-at