By Anei Ochan-Thou, Zheng Cheng Zhu, Lahiru Amaratunge

The brachial plexus. The harbinger of nightmares for all medical students (and junior doctors alike)

For me, I found it hard to conceptualise this phenomenally difficult yet important part of upper limb anatomy. Like many things in anatomy, the more practice and revision that is done, the easier it becomes to understand. In this article,we are going to break down the brachial plexus into smaller chunks so hopefully you can leave with a better understanding of it.

First stop, what is the brachial plexus?

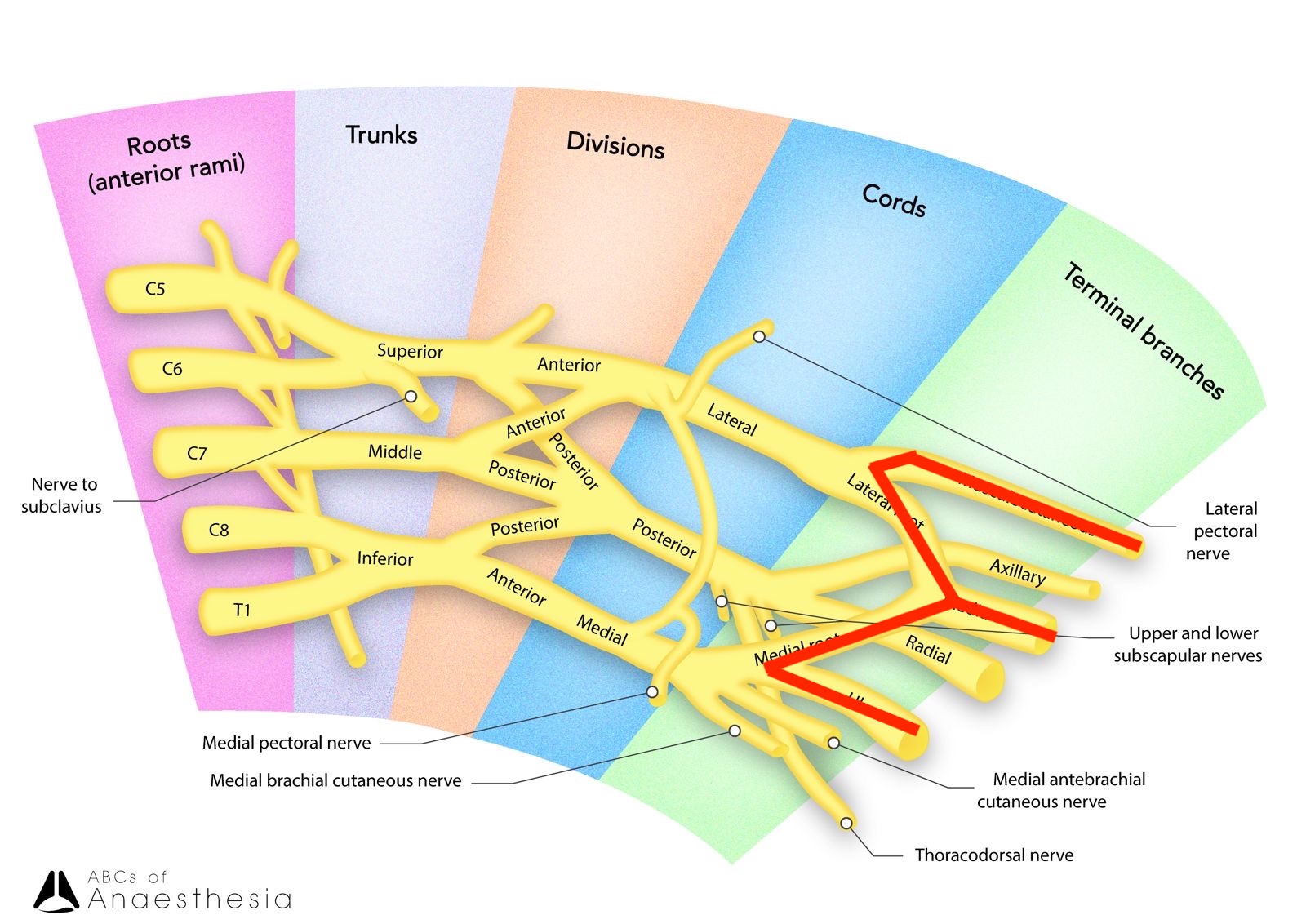

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerves arising from nerve roots C5 and T1 that ultimately gives rise to all the nerves that innervate the upper limb – both sensory and motor fibres – including arm, forearm, hand, shoulder, axilla, and some areas of the chest. From the spinal roots all the way to the peripheral nerves, the brachial plexus begins from the spinal nerves of C5 to T1 (roots or the ventral rami), then trunks, divisions and then cords. All throughout the brachial plexus smaller branches of nerves branch off to supply muscles and skin of the shoulder and superior thorax region.

Let’s delve into each component

The five roots run deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and make their way between the anterior and middle scalene muscles in between the clavicle and 1st rib.The roots then intercalate to form the superior middle, and inferior trunks, which then divided into the anterior and posterior divisions. Drawing the brachial plexus is an excellent way to detangle the verbal descriptions and better visualise and understand the roots, divisions, and cords.

One of the ways I try to remember the stages of the brachial plexus is through the acronym ‘Really Tired? Drink Coffee.’ Roots Trunks Divisions Cords.

Ultimately the parts of the brachial plexus that enter into the axilla are the anterior and posterior divisions, which give rise to the lateral, medial and posterior cords winding along the axillary artery and forming an intimate relationship. I find it easier to visualise the divisions and cords in relation to the axillary artery. For example, the posterior division will be located relatively posterior to the axillary artery.

See that M shape when the cords begin to form? You should always look for that as it helps to orient yourself as to where you are. M for median nerve, and hence, the middle cord of the M will be the median nerve, the lateral cord will be the musculocutaneous and the medial cord will be the ulnar nerve. Once you find this ‘M’ then you’ll know what nerves form from these cords.

The main nerves of the upper limb rise from the lateral, medial and posterior cords. These nerves are the musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, radial, and axillary nerves.

Clinical implications of nerve blocks and injuries

When thinking about the consequences of injury or damage of the peripheral nerves, knowing its motor and sensory supply goes a long way into ascertaining the impairment of each and what results from regional anaesthesia to these nerves. Below we will go into all of these nerves, briefly, and what happens when it is damaged.

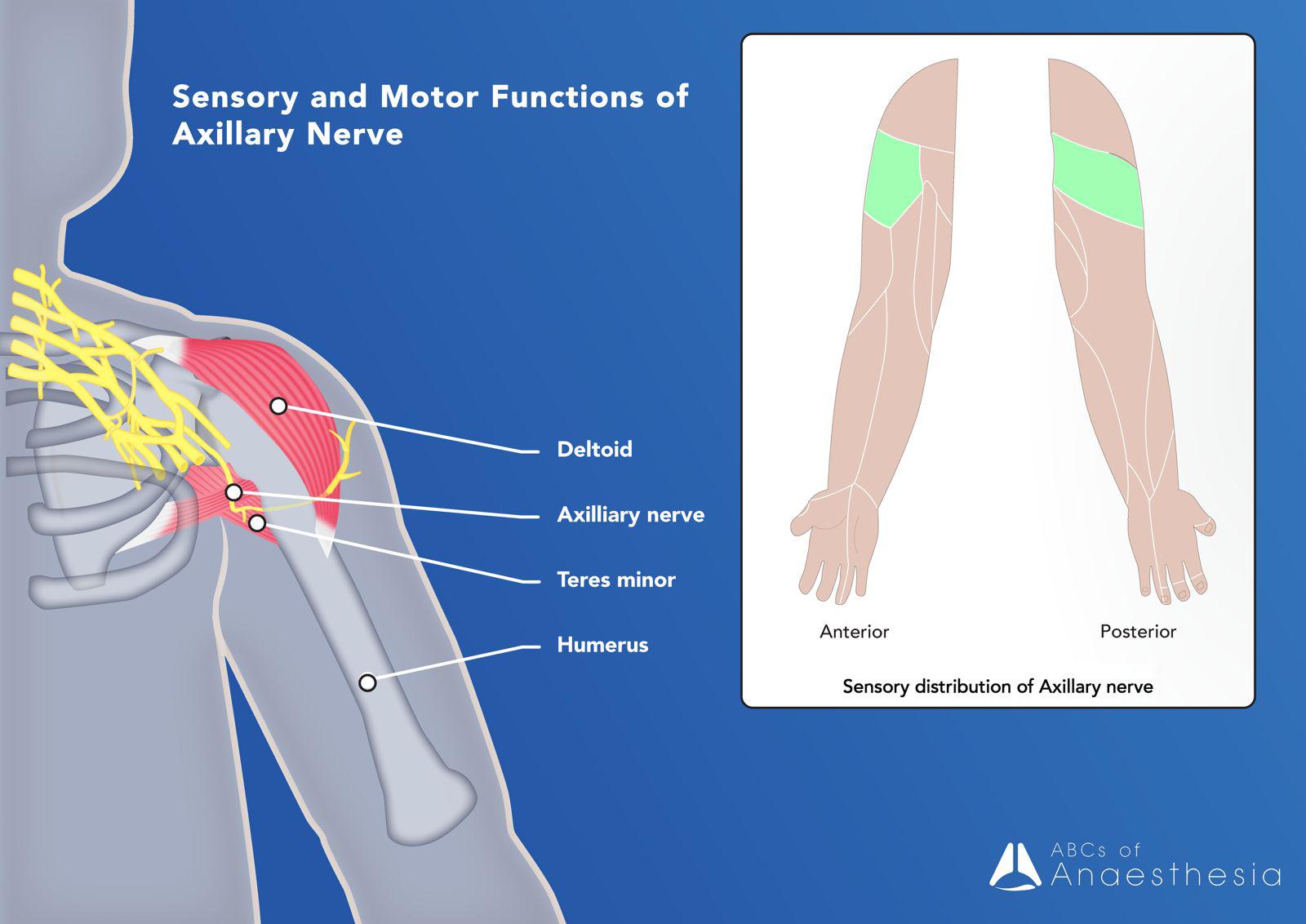

Axillary Nerve: branching from the posterior cords and running posterior to the surgical neck of the humerus. Innervating the deltoid and teres minor muscles and the skin/joint capsule of the shoulder.

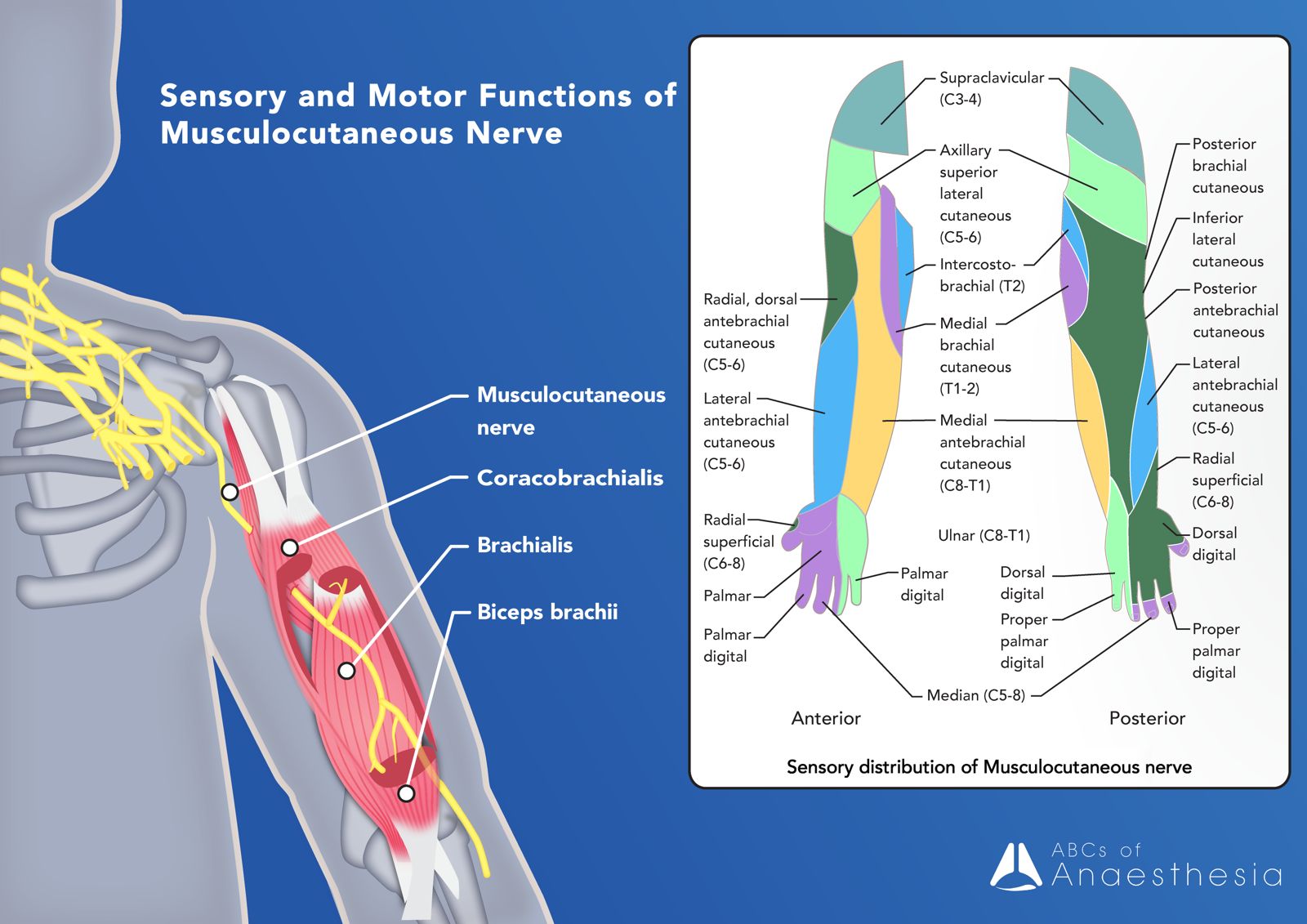

Musculocutaneous Nerve: a major branch from the lateral cord, making its way through the anterior arm and supplying motor innervation to the biceps brachii, brachialis and coracobrachialis muscles. Beyond the elbow, its sensory innervation is the lateral forearm, hence the ‘cutaneous’ aspect of the musculocutaneous nerve.

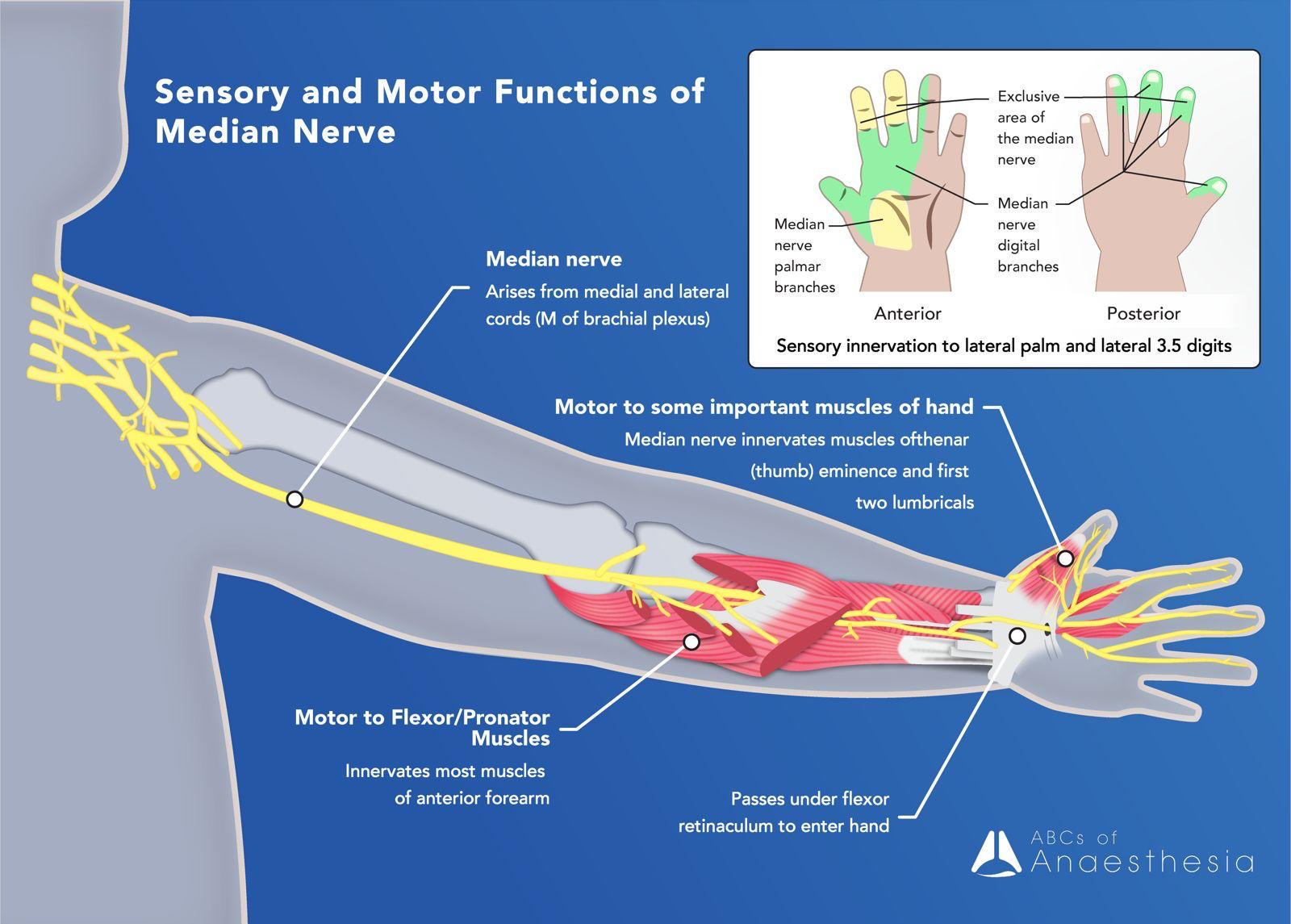

Median Nerve: a very important nerve, the median nerve makes its way to the anterior forearm, traversing through the cubital fossa, supplying sensory fibres to the skin of the forearm and motor to the majority of muscles in the flexor compartment of the forearm. Additionally, it innervates the five intrinsic muscles of the lateral palm and has sensory fibres to 3 ½ lateral digits.

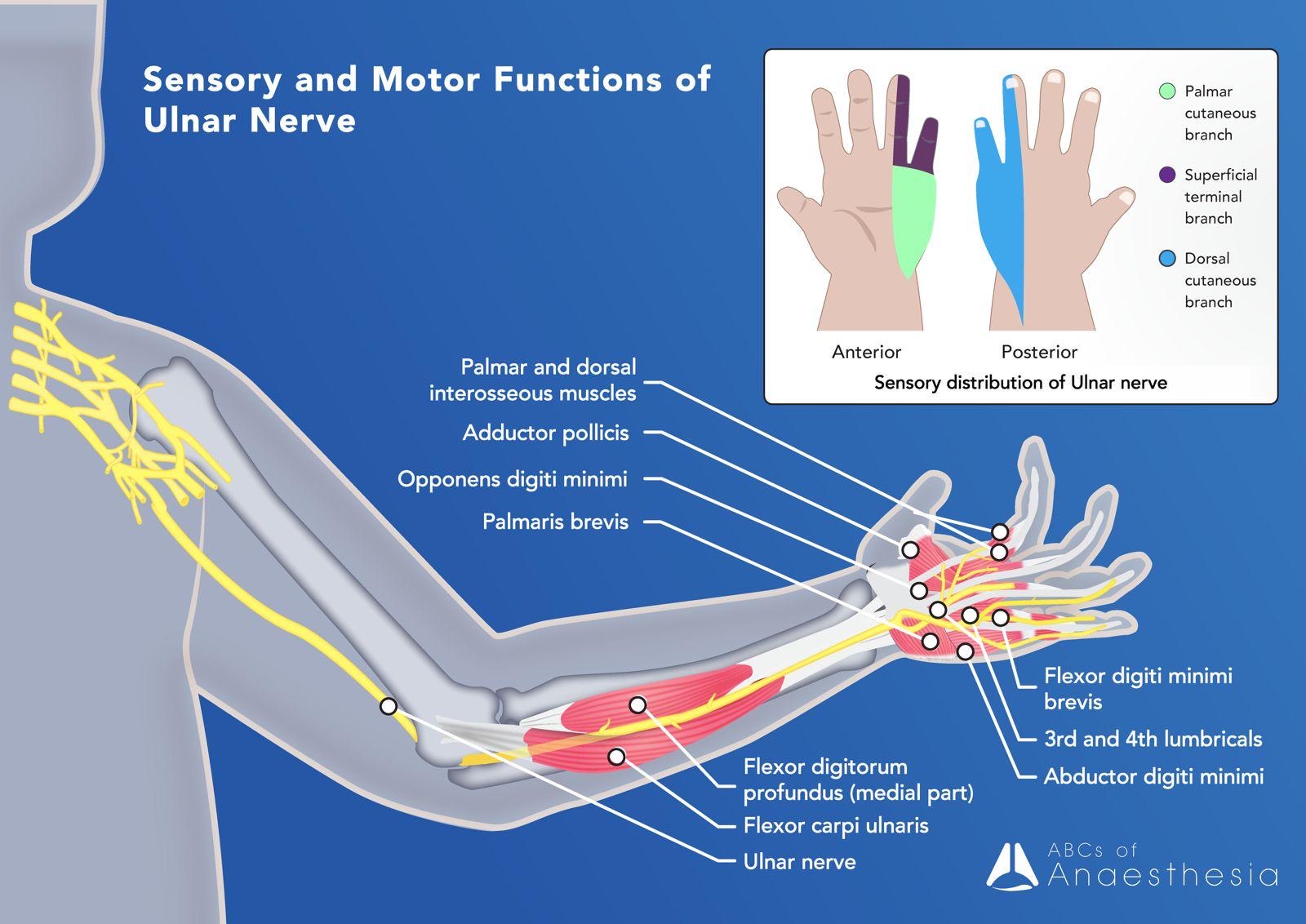

Ulnar Nerve: From the medial cord, the ulnar nerve descends into the forearm, behind the medial epicondyle and follows the course of the ulnar bone into the arm where it innervate the majority of the intrinsic hand muscles and sensation to the palmar and dorsal aspect of the medial 1 ½ digits. In the forearm it supplies the flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial part of the flexor digitorum profundus (the median nerve supplies the lateral aspect of the flexor digitorum profundus).

Radial Nerve: The radial nerve continues as an extension of the posterior cord and wraps around the humerus within the radial groove. Supplying the posterior skin of the dorsum of the hand and the posterior skin of the arm and forearm. It supplies

motor fibres to all the extensor muscles of the upper limb.

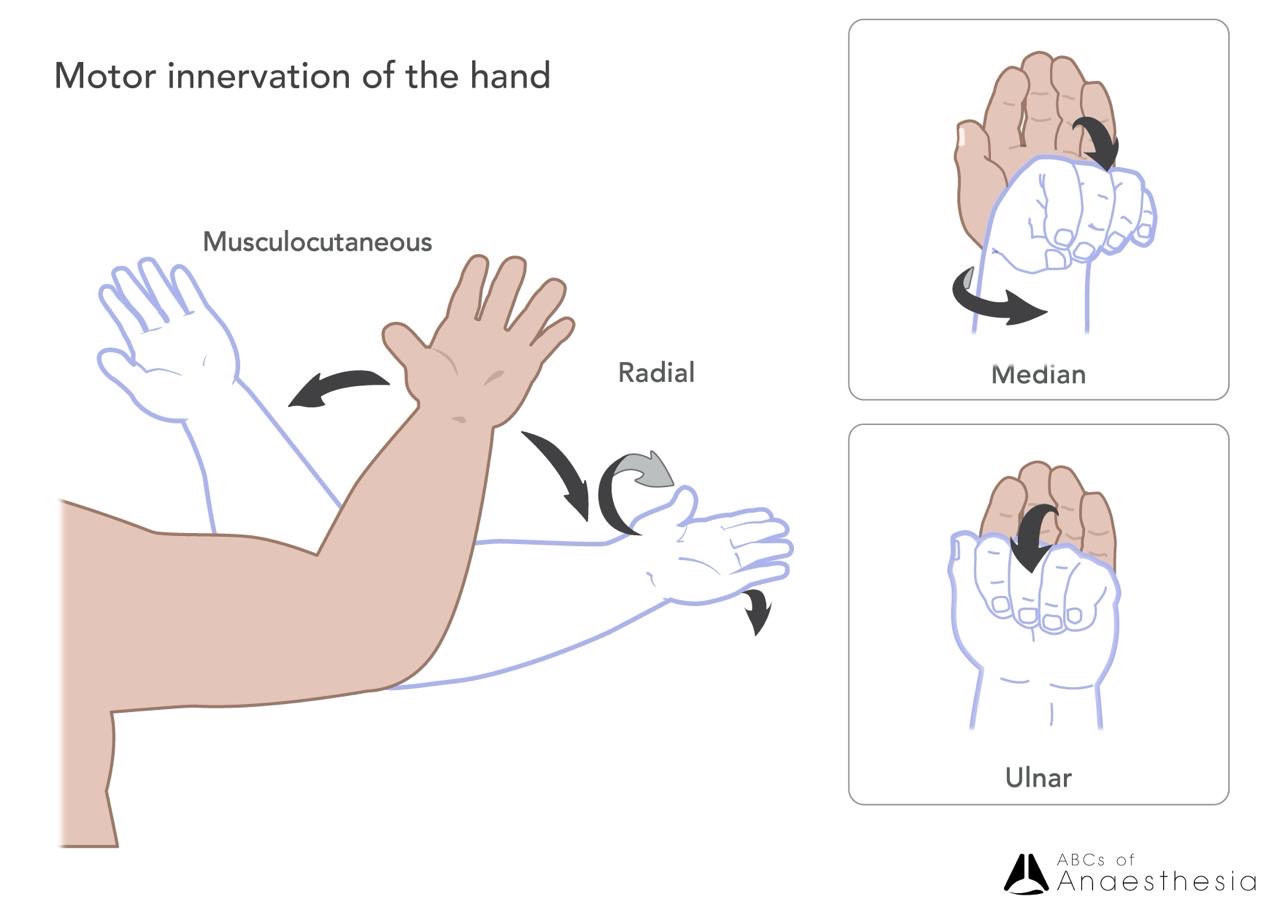

Ultimately, to test the peripheral nerves of the upper limb during an examination, you can quickly test the motor and sensory distribution in the following way:

Musculocutaneous – Flexion of the arm.

Radial – Supination and pronation.

Median – Flexion of the wrist.

Ulnar – Flexion at the interphalangeal joints.

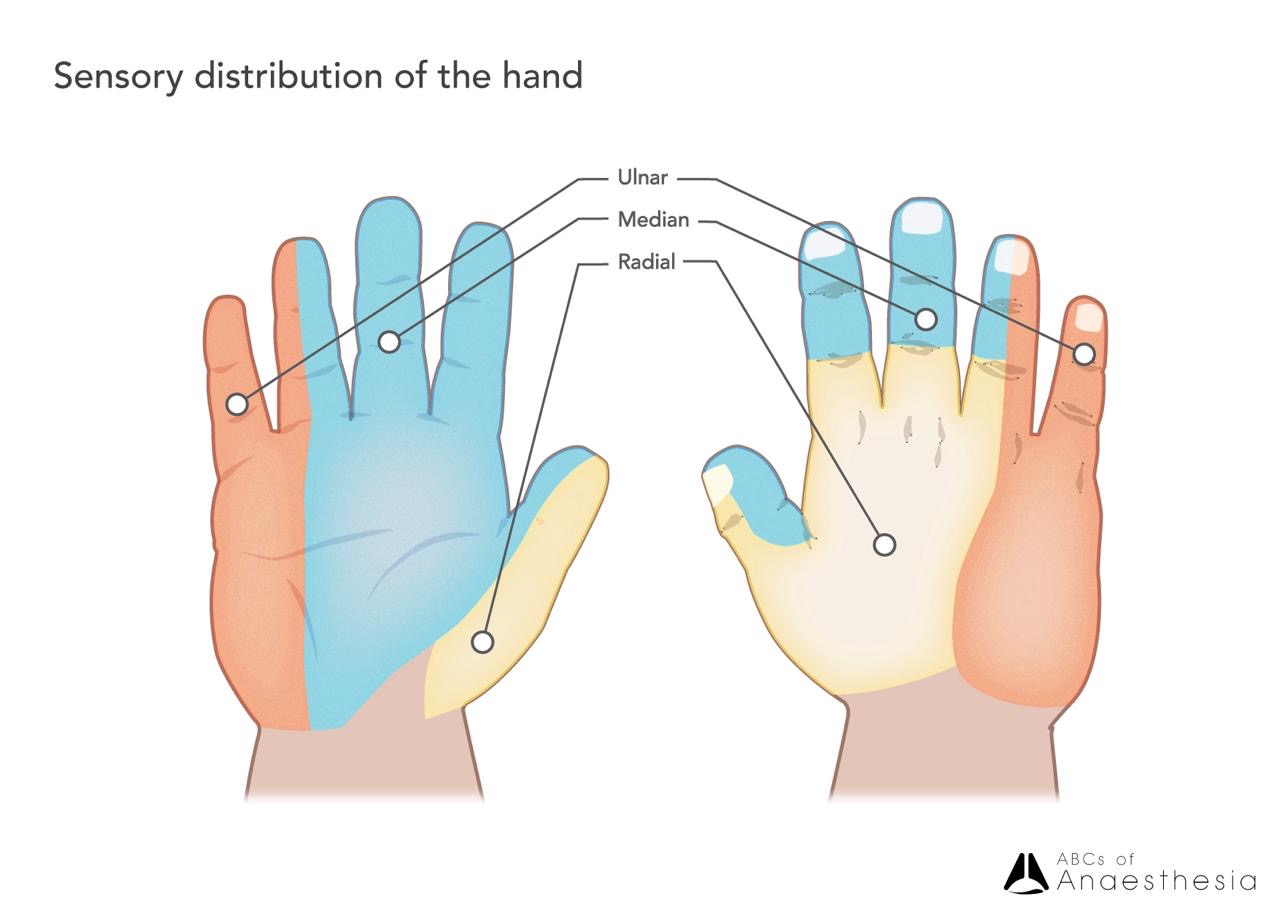

Ulnar – Medial ½ digits and palmar surface of the hand.

Median – Lateral three and a half digits and palmar surface of the hand.

Radial – Majority dorsum of the hand.

Classic brachial plexus injury patterns

By Zheng Cheng Zhu

Erb palsy

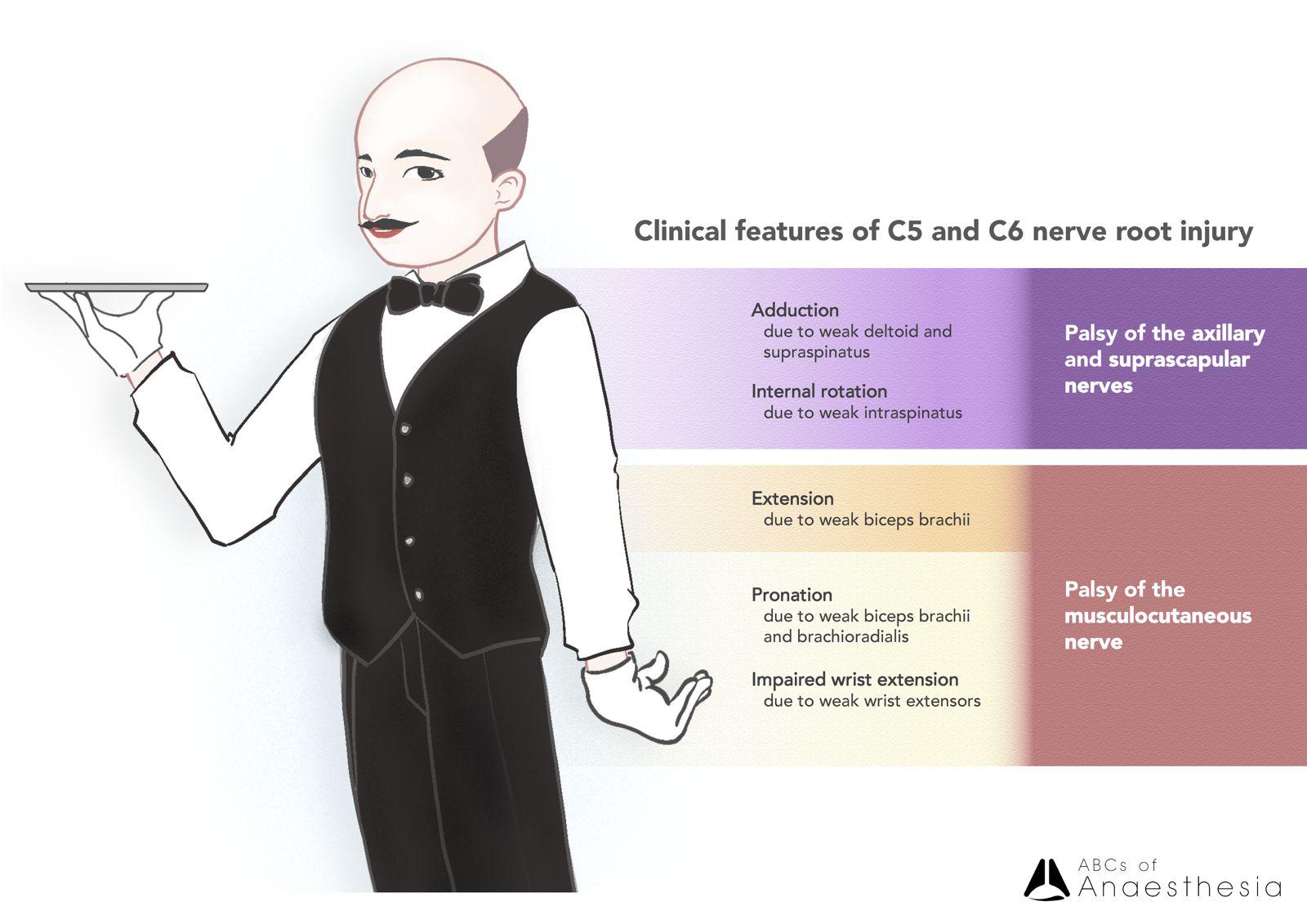

You meet Mr. Smith, 25 yo gentleman, BMI 36, awaiting his left knee ACL repair. You note his right arm is held in a “waiter’s tip” position, with thinning of his shoulder muscles. He reports he has had weakness in his arm since childbirth…

Erb palsy, secondary to injury to the ipsilateral C5 and C6 nerve roots, typically occurs from excessive shoulder-neck distraction forces, most commonly encountered during difficult vaginal birth with macrosomia and shoulder dystocia preventing delivery of the superior shoulder.

C5 and C6 provide motor supply to deltoid (axillary), bicep brachii and brachialis muscles (musculocutaneous), and injury to these nerve roots correspondingly result in weakness in

-

Shoulder abduction

-

Shoulder and elbow flexion

-

Shoulder external rotation

-

Wrist supination

This results in the classical “waiter’s tip”, where the affected arm is held in unopposed adduction and internally rotated, with elbow extended, wrist pronated and palm facing outwards.

Klumpke palsy

You meet the next patient, Ms. Kim. She’s 35yo, left handed, having unfortunately fractured her left wrist and is awaiting her open reduction internal fixation. She tells you she was originally right handed, but after her bike accident 10 years ago she lost strength in her right hand and has a “claw hand”…

Klumpke palsy occurs from injury to the C8 and T1 nerve roots or the inferior trunk, typically from abrupt hyperabduction of the ipsilateral shoulder, like those sustained in high-force trauma.

C8 and T1 supplies the intrinsic muscles of the hand, including the lumbricals and interosseous muscles. Weakness of these muscles result in unopposed hyperextension at the metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion at the interphalangeal joints from extrinsic hand muscles, resulting in the classical “claw hand” deformity.

That’s a brief overview of the brachial plexus and remember, if you’re really tired, drink coffee!

In future articles, we will be delving into the specific upper limb regional blocks that can be performed, and now that we have an understanding of the brachial plexus, the regional blocks will extend on this knowledge.

References:

Basit H, Ali CDM, Madhani NB. Erb Palsy. [Updated 2023 Apr 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513260/

Merryman J, Varacallo M. Klumpke Palsy. [Updated 2023 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531500/

Marieb E.,, Hoehn, K. Human Anatomy and Physiology. Pearson Education. 2012.