By Zheng Cheng Zhu

Key reference:

Uppal V, Russell R, Sondekoppam R, et al. Consensus Practice Guidelines on Postdural Puncture Headache From a Multisociety, International Working Group: A Summary Report. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2325387. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25387

Quick Summary

-

Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) develops within 5 days of a neuroaxial intervention.

-

PDPH often postural with improvement on laying flat.

-

Neck stiffness and hearing changes are common associated symptoms.

-

Risk factors for PDPH include:

-

Younger age, female sex

-

Use of larger gauge spinal needle

-

Use of cutting edge spinal needle

-

-

PDPH is hypothesised to be caused by meningeal stretch that occurs with the pressure differential created by cerebrospinal fluid leak.

-

Prophylaxis techniques against PDPH have limited evidence, and should be considered on a benefit-risk basis.

-

Like all pain management, PDPH management should focus on biopsychosocial approach, with non-pharmacological and pharmacological multimodal analgesia.

-

Invasive techniques, such as epidural blood patch (EBP), should be considered for severe PDPH unresponsive or refractory to first-line management limiting daily function.

-

Patients suffering PDPH are at risk of serious long-term complications, and close follow-up and safety-netting should form part of patient’s management.

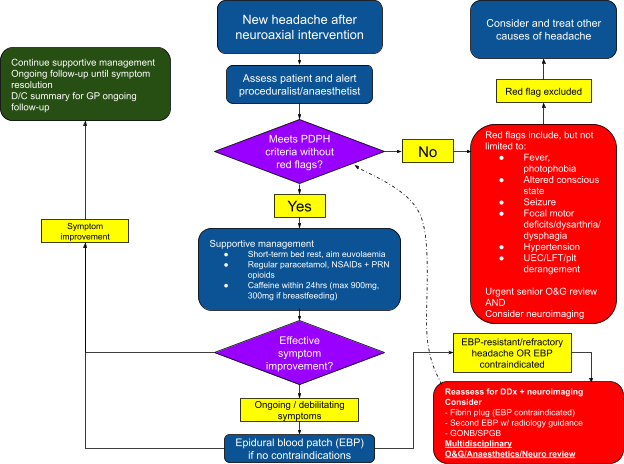

See appendix 1 for flowchart summarising the assessment and management of PDPH.

Preamble

You are an anaesthesia trainee at a regional hospital on your obstetric term. You are called by Obstetrics regarding Ms. LP, a 26yo G2P2, otherwise well lady who is D2 post uncomplicated vaginal birth for her second boy. You remembered Ms. Smith from your night shift, when you inserted an epidural to assist her labour.

“This headache is killing me!”

She has unfortunately developed a terrible headache and a stiff neck since last night. It is particularly worse when she gets up from her bed, to the extent that she is now apprehensive of sitting up to breastfeed her newborn. She otherwise reports no other neurological symptoms or photophobia, and examines without focal deficits. Her vitals do not show signs of pre-eclampsia, infection, or sequelae of post-partum haemorrhage. Her biochemical markers are also within normal limits.

Obstetrics has commenced paracetamol and ibuprofen with PRN endone, however with minimal effect. Obstetrics is concerned that Ms. LP has developed post dural puncture headache that is limiting maternal and neonatal wellbeing.

What is Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH)?

Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is a common iatrogenic complication of dural breach after neuroaxial intervention. According to 2018 definition by International Headache Society (IHS), PDPH is defined as a headache that develops:

-

5 days after an intentional (e.g spinal anaesthesia, diagnostic lumbar puncture) or unintentional (e.g. epidural catheter insertion) dural puncture;

-

Commonly accompanied by neck stiffness or auditory symptoms;

-

Has postural component, with improvement on laying flat;

-

Self-remits after 2 weeks.

Other neurological symptoms such as midline back pain, visual disturbance and vertigo have also been associated with PDPH.

Post-partum headache is a non-specific symptom and can signal more sinister differential diagnoses, such as meningoencephalitis, pre-eclampsia, intracranial pathology and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. A detailed history and examination is therefore imperative, and any red flags such as altered conscious state, focal neurology, deranged biochemistry and headache despite adequate PDPH headache should warrant urgent reconsideration and review.

While the overall incidence of PDPH ranges between 0.5% to 0.7% following all neuroaxial procedures, it occurs up to >80% in patients with accidental dural breach during epidural insertion, impacting disproportionally our obstetric population. Its potential to cause post-partum complications in the form of delayed recovery, prolonged hospital stay, impaired maternal-infant bonding and psychological distress underscores the need for its effective and standardised management.

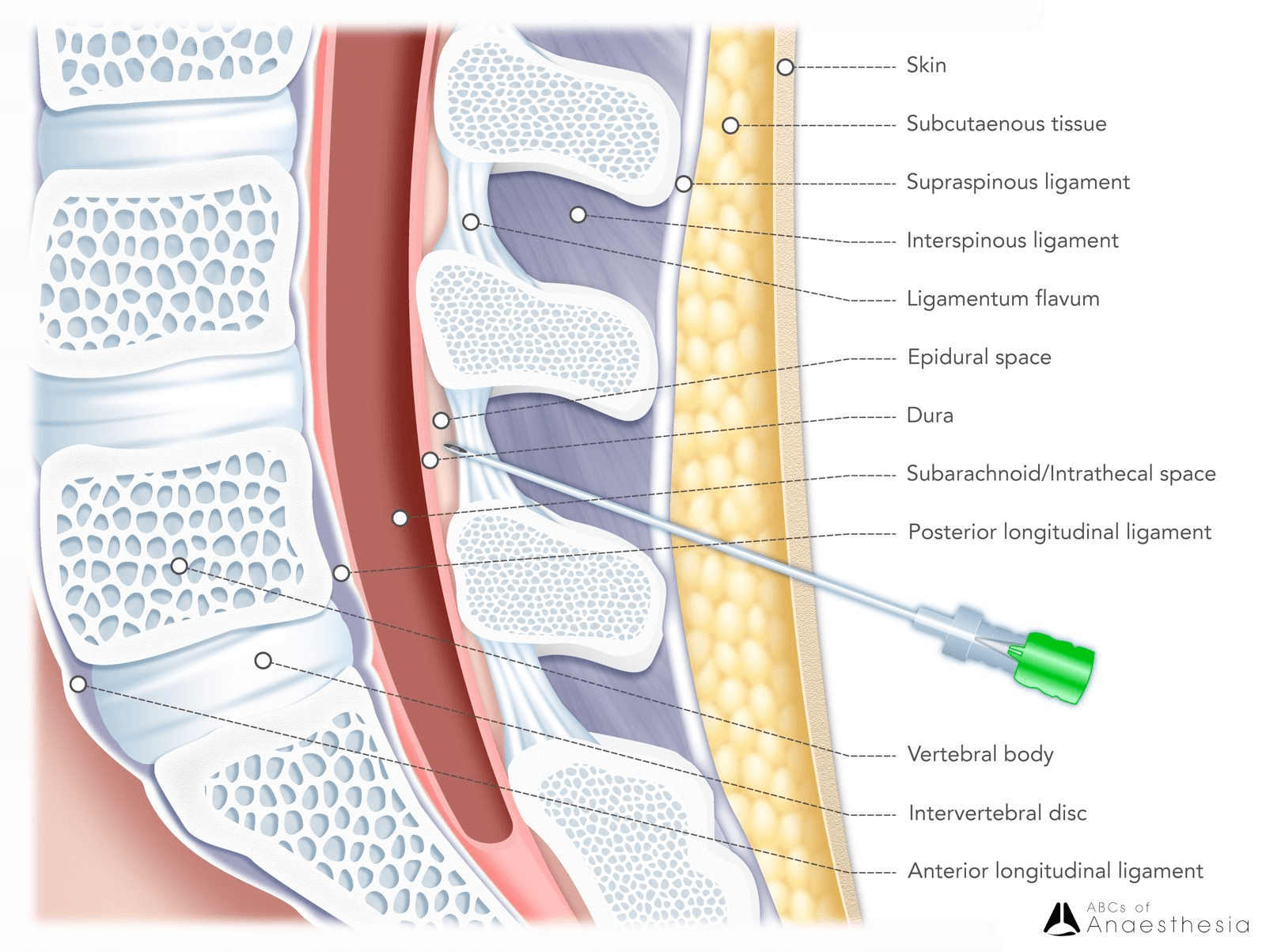

Proposed pathophysiology of PDPH

As part of IHS’s definition, PDPH is widely thought to be caused by low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure from CSF leak, leading to meningeal stretch and activation of CNS nociceptive centres. Depleted CSF volume may also cause compensatory cerebral vasodilation and increased cerebral blood flow implicated in headache.

Who is at risk of PDPH?

Important patient and procedural risk factors have been identified by the 2023 Consensus Guidelines:

|

Patient factors |

Procedural factors |

|

Young age Female sex Previous PDPH, chronic headache |

Cutting needles (instead of non-cutting types) Larger gauge needles (cutting needles only) Multiple procedural attempts Operator inexperience Erect patient positioning |

Of patient factors, younger age and female sex have been strongly associated with development of PDPH. Unsurprisingly, these factors correspond with the majority of our obstetric patients. They routinely receive neuroaxial intervention in the form of epidural analgesia and spinal anaesthesia as part of their labour or caesarean management.

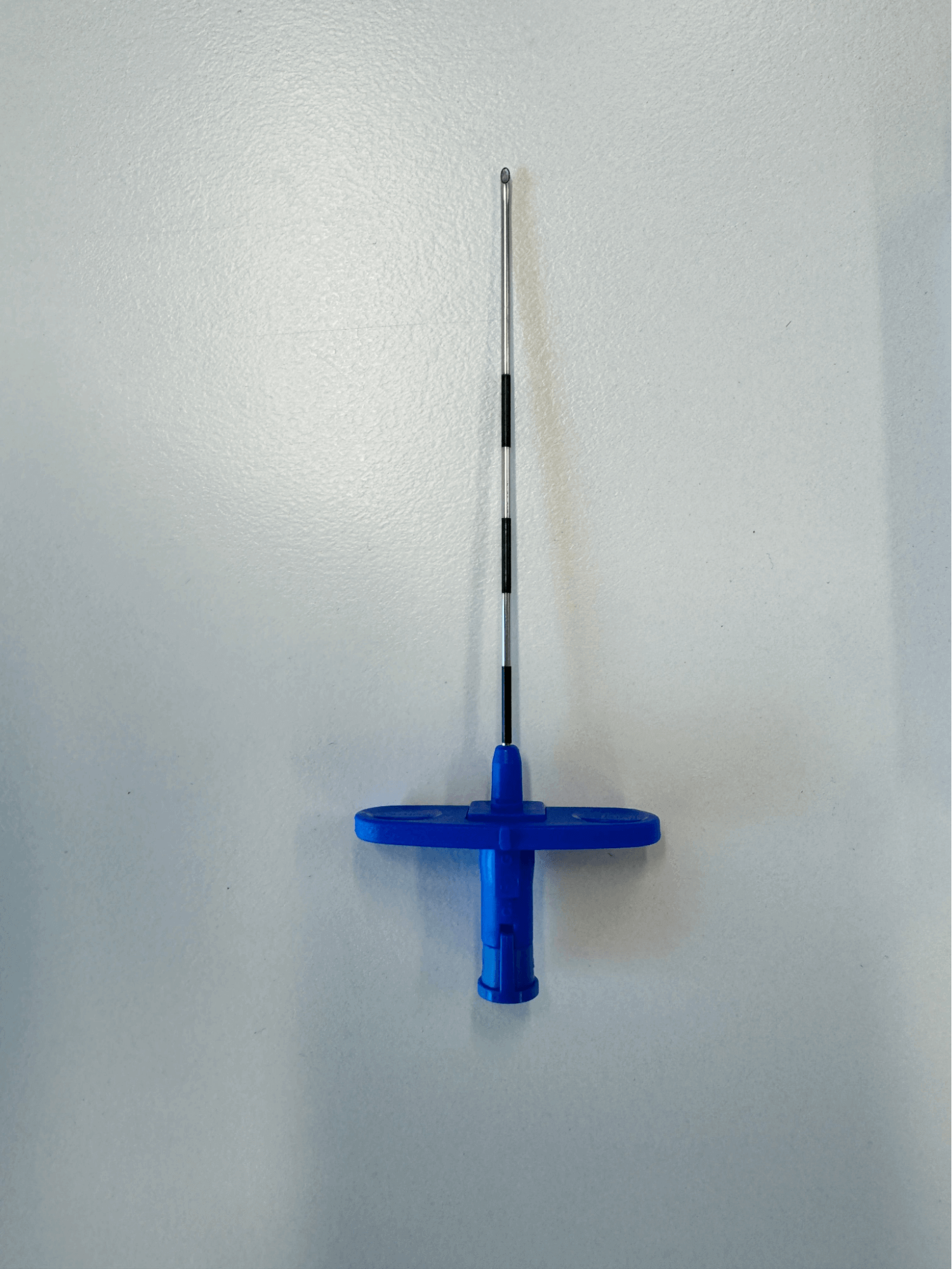

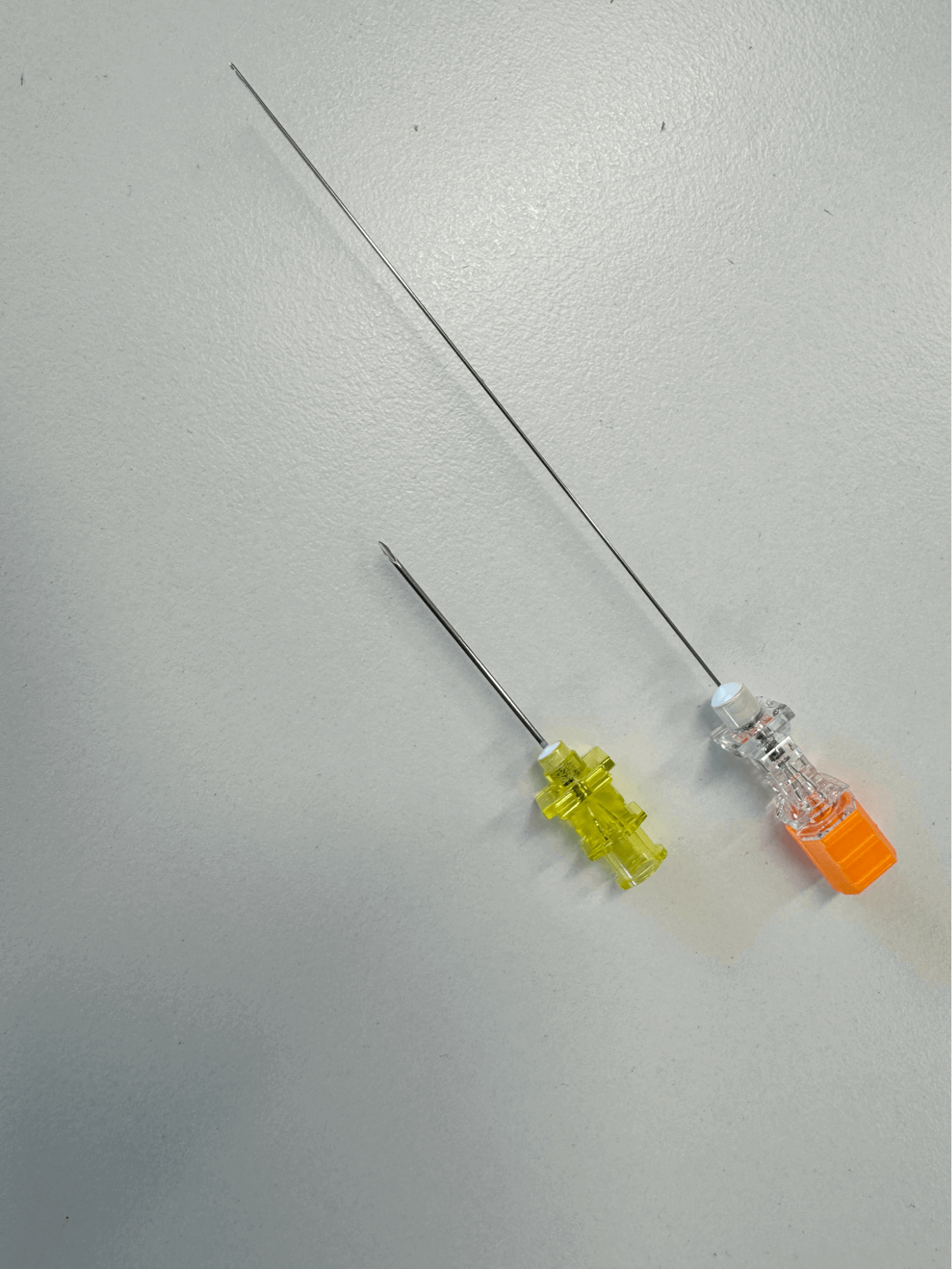

Procedurally, use of cutting-edge needles has been associated with much higher risk of PDPH, with larger gauge needles proportionally compounding the risks. In a meta-analysis of 32 randomised controlled trials by Zorrilla-Vaca et al. (2018) comparing pencil-point non-cutting needles with cutting needles, there was a 59% risk reduction favouring pencil-point needles. While there was a direct correlation between gauze size and PDPH risk for cutting needles, this was not the case for pencil-point needles. In the case of PDPH, the technical disadvantages of pencil-tip needles are offset by superior tactile dura recognition and reduced dural trauma compared to cutting needles.

Similarly, operator familiarity and technical factors resulting in multiple instrumentation attempts increase the risk of larger and multiple unintended dural punctures.

Is there effective prophylaxis for PDPH?

Addressing procedural risk factors to avoid unintended dural puncture and trauma is the most efficient and cost-effective PDPH prevention strategy. Anaesthesia departments are encouraged to increase simulated and supervised practice of neuroaxial interventions, and setting practice guidelines to discourage the use of cutting needles unless clinically indicated.

In circumstances where dural puncture has occurred, whether intentional or iatrogenic, there have been numerous prophylaxis techniques described with varying evidence base.

Intrathecal catheter insertion

After unintentional dural breach is recognised during epidural insertion, instead of reattempting epidural insertion at the same or different spinal level, anaesthetists can opt to insert the catheter intrathecally to occlude the dura defect whilst delivering adequate analgesia intrathecally, thereby limiting CSF leak. A meta-analysis by Heesen et al. (2019) of 13 studies concluded an 18% reduction in incidence of PDPH, and a 38% reduction in incidence of providing epidural blood patch for severe PDPH. Although the authors were unable to confidently exclude Type I error from its trial-sequential analysis, there is nevertheless evidence that intrathecal catheterisation may be able to decrease the occurrence and severity of PDPH.

The 2023 Consensus Guideline recommends in cases of inadvertent dural puncture during epidural insertion, intrathecal catheter insertion may be considered on balance of risk, such as infection and drug-related side effects.

Prophylactic epidural blood patch

Whilst the therapeutic role of epidural blood patch (EBP) in PDPH is well-established, evidence is scarce for its routine application in preventing PDPH after accidental dural puncture.

The 2023 Consensus Guideline recommends against its routine use, in light of variable incidence of PDPH post dural puncture and risk of subjecting patients to unnecessary harm associated with EBP insertion.

Prophylactic bedrest

Owing to the postural component of PDPH, some have suggested prophylactic bedrest as means of minimising severity, and preventing PDPH altogether. It theoretically limits fluctuations in CSF hydrostatic pressure and promotes dural healing and cessation of CSF leak.

Unfortunately, available evidence does not support its routine use. A Cochrane review of 24 trials in 2016 failed to demonstrate significant reduction in incidence of PDPH compared to immediate mobilisation. In light of thromboembolic risks associated with prolonged immobilisation, the 2023 Consensus Guideline does not support bedrest for PDPH prophylaxis

Novel epidural and intravenous prophylaxis

Hydroxyethyl starch (HES), a synthetic starch colloid solution used in intravenous volume replacement, has been trialed as an epidural injection to prevent PDPH, with similar mechanism of action as an EBP in plugging the dura hole, and may be used when EBP is contraindicated. A small retrospective analysis of 105 post-partum patients by Zhou et al. (2023) demonstrated a promising prophylactic effect of combined HES-epidural administration post initial dural puncture (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.006-0.143). Again, sufficient comparative data has yet to emerge to support its routine application.

Cosyntropin, a synthetic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) derivative, has been used intravenously to prevent PDPH, through stimulating CSF production to compensate for post-dural puncture leak. Recent published retrospective analysis in 2023 has failed to demonstrate cosyntropin’s efficacy in preventing PDPH.

How do we manage PDPH?

Similar to management of other headaches, management of PDPH should be structured, multimodal, underlined with a biopsychosocial approach to ensure patient-centered care.

In severe cases of obstetric PDPH, mothers can be significantly debilitated with detrimental effects on breast-feeding, maternal mood and maternal-infant bonding, resulting in distress, increased risk of post-partum anxiety, depression, and heightened pain sensitivity. Psychological and maternal support are therefore equally paramount in the holistic management of PDPH.

Medical management should be based on multimodal supportive and pharmacological management, with escalation to invasive interventions in severe cases. The 2023 Consensus Guideline provides the following recommendations:

|

Supportive management |

|

Bed rest Rationale:

Recommendation:

Fluid status Rationale:

Recommendation:

Abdominal binders and aromatherapy Rationale:

Recommendation:

|

|

Pharmacological management |

|

Multimodal analgesia Rationale:

Recommendation:

Caffeine Rationale:

Recommendation:

|

|

Invasive interventions |

|

Epidural blood patch Rationale:

Recommendations:

Epidural fibrin glue (EFG) Rationale:

Recommendations:

Regional nerve blocks (greater occipital nerve block (GONB) and sphenopalatine ganglion block (SPGB)) Rationale:

Recommendation:

|

What are long-term effects of PDPH?

Beyond its immediate morbidity, there is growing evidence to suggest PDPH is associated with chronic and severe sequelae, including chronic headache, backache, neckache, cranial nerve palsies. Life-threatening complications causing death, such as subdural haematoma and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, has been described in isolated case reports, and may be caused by CSF hypotension-related extramural tension on subdural bridging veins and sinus vessels.

Therefore, it is imperative that patients who experience PDPH are closely monitored until symptoms resolve. Primary care physicians should be instructed to continue the patients’ long-term monitoring. Patients should be counseled on the risks of chronic and serious sequelae, and safety-netted to seek urgent medical attention should patients develop new focal neurology, recurrence or change in headache.

Implications

You inform your consultant that Ms. LP has severe PDPH that has failed conservative management, and both of you agree that she may benefit from an EBP, without obvious contraindications such as evidence of sepsis that one would argue otherwise.

You consent her of the risks of PDPH, including the immediate risk of failed procedure, worsening of her symptoms, more dural punctures, bleeding and infection. She agrees to the procedure.

Thankfully, under the supervision of your consultant, you successfully inject 20mls of autologous blood into her epidural space, one level below your original epidural site, without any complications. Over the next few hours, Ms. LP’s headache improves, and by the next day, her headache has resolved. She is grateful for the procedure, as she can now fully devote herself to looking after her baby boy.

You counsel her that, while her headache might be gone, she is at a slightly higher risk of developing long-term or serious complications. You instruct her that she should seek immediate attention if she feels her headache coming back or have any other neurological signs. You kindly instruct the Obstetric resident to document this in Ms. LP’s discharge summary to inform her GP to continue her ongoing monitoring.

PDPH remains the most common complication post neuraxial intervention that affects our obstetric population. Despite numerous investigations into PDPH prophylaxis and novel management, most have unfavourable outcomes or sufficient robust evidence to support their routine use, and current gold-standard management continues to be fraught with undesirable risks. As such, anaesthetists should aim to minimise procedural risk factors of PDPH as the most cost-effective preventative strategy, with ongoing research into novel therapies to hopefully provide effective and less invasive management techniques.

Appendix 1: Flowchart for assessment and management of PDPH

References

Al-Hashel, J., Rady, A., Massoud, F., & Ismail, I. I. (2022). Post-dural puncture headache: a prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and clinical characterization of 285 consecutive procedures. BMC neurology, 22(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02785-0

Arevalo-Rodriguez, I., Ciapponi, A., Roqué i Figuls, M., Muñoz, L., & Bonfill Cosp, X. (2016). Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD009199. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009199.pub3

Bradbury, C. L., Singh, S. I., Badder, S. R., Wakely, L. J., & Jones, P. M. (2013). Prevention of post-dural puncture headache in parturients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 57(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12047

Heesen, M., Hilber, N., Rijs, K., van der Marel, C., Rossaint, R., Schäffer, L., & Klimek, M. (2020). Intrathecal catheterisation after observed accidental dural puncture in labouring women: update of a meta-analysis and a trial-sequential analysis. International journal of obstetric anesthesia, 41, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2019.08.001

Liu, M., Mitchell, A., Palanisamy, A., & Singh, P. M. (2023). Role of cosyntropin in the prevention of post-dural puncture headache: a propensity-matched retrospective analysis. International journal of obstetric anesthesia, 56, 103922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2023.103922

Park, M., Yu, H., Park, J., Sohn, J. T., Park, K. E., Hwang, Y., Kim, S., & Ok, S. H. (2021). Reinforced conservative management of post-dural puncture headache in a patient with a rare case of tethered cord syndrome using an abdominal binder: A case report. Clinical case reports, 9(3), 1215–1219. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.3733

Thon, Jan N.a; Weigand, Markus A.a; Kranke, Peterb,∗; Siegler, Benedikt H.a,∗. Efficacy of therapies for post dural puncture headache. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology ():10.1097/ACO.0000000000001361, February 20, 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001361

Uppal V, Russell R, Sondekoppam R, et al. Consensus Practice Guidelines on Postdural Puncture Headache From a Multisociety, International Working Group: A Summary Report. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2325387. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25387

Zhou, Y., Geng, Z., Song, L., & Wang, D. (2023). Epidural hydroxyethyl starch ameliorating postdural puncture headache after accidental dural puncture. Chinese medical journal, 136(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001967

Zorrilla-Vaca, A., Mathur, V., Wu, C. L., & Grant, M. C. (2018). The Impact of Spinal Needle Selection on Postdural Puncture Headache: A Meta-Analysis and Metaregression of Randomized Studies. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine, 43(5), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000775