By Nicola Wevling, Zheng Cheng Zhu

Key reference:

Verret, P et al (2024). Intraoperative pharmacological opioid minimization strategies and patient-centred outcomes after surgery: A scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 132(4), 758-770. https://www.bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(24)00009-6/fulltext

Quick summary:

-

Intraoperative opioid minimisation forms part of the broader multidisciplinary effort to reduce opioid-related complications, misuse, and overuse at patient, community, and health system levels.

-

Robust evidence supporting novel opioid-sparing “balanced” anaesthesia techniques in patient-centred outcomes remains lacking

-

Based on the evidence available, the scoping review identified three promising analgesia methods for opioid minimisation:

-

dexmedetomidine,

-

systemic lidocaine

-

COX-2 inhibitors.

-

-

Less promising opioid alternatives investigated included ketamine, paracetamol, and gabapentinoids.

-

There is limited research into the impacts on high-risk population groups.

-

3% of studies investigated geriatric surgical populations.

-

<1% of studies investigated patients with either a chronic pain history or preexisting long-term opioid use.

-

Preamble:

You are an anaesthesia trainee about to review Mr. LC for your morning list. He is a 60-year-old gentleman, BMI 27, here for his elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He has no significant past anaesthetic complications or postoperative nausea and vomiting. He is otherwise fit and well apart from a worsening chronic lower back pain which is currently managed with paracetamol and ibuprofen. .

“I’m scared that my back will kill me after the surgery. Any chance you can give me some strong painkillers to get me through the surgery and going home?

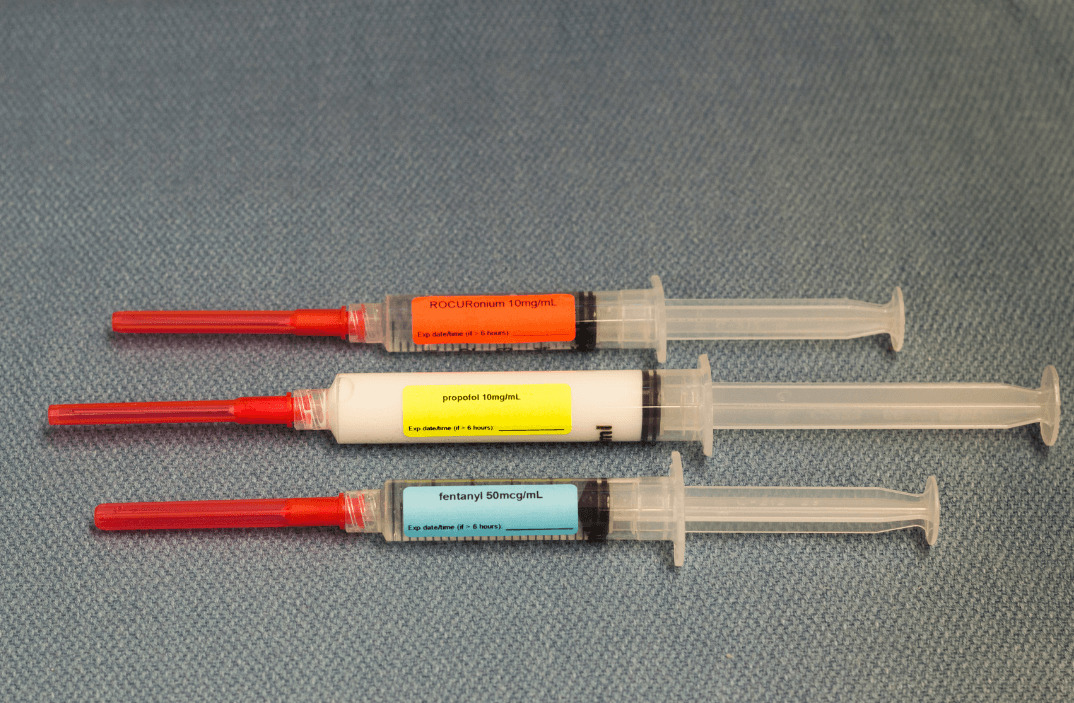

You consider Mr. LC’s request and raise this with your consultant, correctly highlighting the potential risks and benefits of utilising opioids intraoperatively for this patient. You ask if there are potential alternatives that can minimise Mr. LC’s opioid use.

Introduction

Opioid minimisation has gained increasing traction in light of the escalating health burden of problematic opioid misuse and overdose-related morbidity and mortality, stemming in part from the pervasive overuse of prescription opioids across our health service. As one of the most frequent prescribers, anaesthetists and pain clinicians hold key responsibilities in opioid stewardship and opioid-sparing practice. However, it would be remiss to ignore the therapeutic benefit opioids offer for acute surgical pain, its vital role in multimodal anaesthesia, and post-operative function and recovery. As such the move to reduce opioid usage is not simple.

|

Risks |

Benefits |

|

Adverse effects

Dependence and tolerance

Overdose

|

Providing adequate analgesia which may reduce the risk of

|

Table 1. List of some of the potential risks and benefits of opioid use

Discussion

The decision to utilise perioperative opioids requires careful consideration of patient, surgical, and anaesthetic-related factors relevant to each case.

For Mr. LC, the surgical-related factors in this case of intra-abdominal surgery include the increased risk of postoperative ileus/ pseudo-obstruction making the side effects of nausea, vomiting, and constipation particularly detrimental.

From the anaesthetic and pain management perspective, Mr. LC’s postoperative abdominal pain as well as his preexisting chronic back pain may make deep breathing and mobilisation challenging, meaning that adequate opioid analgesia may be necessary to promote patient comfort, function, and post-operative recovery. Appropriate opioid management of acute post-surgical pain is also important in minimising development of postoperative chronic pain. However, this must be balanced against the short-term and long-term adverse effects of opioids as aforementioned, with a clear immediate plan for symptom management and post-operative monitoring, as well as a clear pathway for timely opioid de-escalation and community follow-up. Patient education and setting of expectations also form part of the biopsychosocial model of pain management, where patients must be counselled on the lack of evidence of opioids for chronic non-cancerous back pain to avert the risk of opioid dependence.

The ideal solution would be for an opioid-sparing alternative that would offer adequate pain relief. Although requiring more evidence, this scoping review by Verret et al. (2024) into the potential replacement therapies offered three promising substitutes; dexmedetomidine, systemic lidocaine, and COX-2 inhibitors. Interestingly, other modalities often reached for in the operating theatre including ketamine, paracetamol, and gabapentinoids offered less encouraging results (see Table 2). According to this paper, there is evidence of change within this field, however robust research is lacking due to, in part, significant inter-institutional heterogeneity in opioid-sparing practice and paucity of multicentre, high-quality trials.

|

Analgesic |

MOA |

Adverse effects/ considerations |

Discussion |

Result |

|

Opioids |

Mu receptor agonist |

Constipation Nausea, vomiting Drowsiness Dependence, tolerance, overdose, death |

Prescription rates in the US have decreased, however there is an increasing number of deaths from overdose. |

N/A |

|

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) |

Not understood well – likely central COX1/ COX2 inhibition |

Hepatotoxicity in overdose Generally considered safe |

Current IV paracetamol shortage (likely short-term) Precaution in liver disease |

More research is required – possibly less promising |

|

COX-2 inhibitors eg. parecoxib |

Selectively inhibits COX-2 mediated prostaglandin synthesis |

Avoid in patients with renal impairment & pregnancy Has better adverse drug reaction profile compared to non-selective COX inhibitors for peptic ulcer disease, asthma, and bleeding |

Decreased inhibition of COX1 which may offset some of the potential for reduced gastric protection as well as anti-platelet effect |

Promising from current data |

|

Local anaesthetic (LA) agents eg. lidocaine |

Voltage-gated sodium channel blockade, stabilising cell membrane inhibiting depolarization of pain fibres |

Allergy Toxicity (CNS and cardiac) Cardiac effect of reduced conduction in patients with pre-existing arrhythmias or bradycardia |

It can be used as regional anaesthesia or systemically which has a higher risk of LA systemic toxicity |

Promising from current data |

|

Ketamine |

NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor antagonist |

Hypertension, tachycardia Muscle tone increase Lacrimation Hypersalivation Nausea, vomiting Raised intracranial and intraocular pressures. Emergence reactions eg hallucination |

It can be used as induction anaesthesia, analgesia, and sedation |

More research is required – possibly less promising |

|

Gabapentinoids eg. gabapentin or pregabalin |

Unclear – alpha-2-delta protein subunit reducing calcium influx and thus depolarisation of pain fibres |

Irritability Respiratory depression Depression Impaired balance Insomnia Constipation Cramps Arthralgia Hallucinations Urinary incontinence Many others |

Interestingly there is a lack of evidence of interaction with the GABA neurotransmitter or its receptor Primarily given orally prior to the procedure, possible to give IV intra-operatively |

More research is required – possibly less promising |

|

Dexmedetomidine |

Alpha 2 and imidazoline agonist Results in hypotensive and antiarrhythmic properties |

Risk of bradycardia and hypotension (especially in the elderly) Fever Headache Dry mouth nausea |

Nil association with respiratory depression

|

Promising from current data |

Table 2. Summary of analgesics discussed in the scoping review

Ultimately, more research is required to determine an appropriate change to practice that would lead to improved patient outcomes. This would require holistic review of patient-centred outcomes along with more objective outcomes such as long-term analgesic requirements.

Notably, looking into short-term or long-term opioid use alone without patient-centred outcomes may be misleading. Opioid requirement may not be a consequence of opioid tolerance or dependence but rather the result of high analgesia requirements. Moreover, opioid use itself may not necessarily lead to poorer health outcomes when compared to alternative therapies. Thus, clinical context is likely required in conjunction with opioid use parameters in order to determine whether there are truly negative impacts of opioids compared to substitute analgesics.

There are indeed benefits of opioid use intraoperatively including haemodynamic stability during general anaesthetic as well as the increased rapid emergence through a reduced required sedative dose as there can be an additive effect of opioids with other hypnotic agents.

Conclusion

You come back to the anaesthetic bay and discuss your pain plan with Mr. LC. You explain that you will be giving him pain relief with opioids during and immediately after his operation as part of his anaesthesia, but also a range of other analgesics such as paracetamol and NSAIDs as part of a multimodal approach to limit the amount of strong opioids needed. You highlight some of the common side effects of opioids, which you hope to control with PRNs for his nausea and vomiting and constipation. You mention that although there are other non-opioid alternatives, they currently don’t have the evidence for you to confidently use safely with proven effectiveness. You set some expectations with Mr. LC, that the aim is not to get Mr. LC pain-free, but to a level that will allow him to do simple tasks and aid his post-op recovery.

Regarding his discharge, you reiterate that opioids, although effective in the short-term for his surgical pain, have no evidence that it would be useful for his chronic back pain, and that long-term use may cause more harm. You recommend that Mr. LC has a discussion with his GP and explore other strategies such as physiotherapy.

Mr. LC is understanding of your explanation and is thankful for your careful consideration of his situation.

…..

More research with subjective outcomes is required to ascertain suitable substitutes to opioids which optimise patient recovery.

Dexmedetomidine, systemic lidocaine, and COX-2 inhibitors were identified as likely promising analgesic candidates.

There is a potential benefit to reducing opioid use given their associated significant adverse effects. However, opioids do offer many desirable properties including haemodynamic stability intraoperatively as well as strong analgesia intraoperatively making this balance difficult.

References:

Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd. (2024). Australian Medical Handbook.

Carley, M. et al. (2021). Pharmacotherapy of the prevention of chronic pain after surgery in adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology, 135 (2), 304-325 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34237128/

DrugBank (2005). Acetaminophen. Retrieved from https://go.drugban k.com/drugs/DB00316

Foo, A et al. (2020). The use of intravenous lidocaine for postoperative pain and recovery: International consensus statement on efficacy and safety. Anaethesia, 76(2), 238-250. https://associationofanaesthetists-publications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/anae.15270

The Lancet (2019). Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: Harms to populations, interventions, and future action. The Lancet, 394(10208), 1560-1579. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32229-9/abstract

Verret, P et al (2024). Intraoperative pharmacological opioid minimization strategies and patient-centred outcomes after surgery: A scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 132(4), 758-770. https://www.bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(24)00009-6/fulltext

Verret, P et al (2020). Perioperative use of gabapentinoids for the management of postoperative acute pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology, 133, 265-279. https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article/133/2/265/109137/Perioperative-Use-of-Gabapentinoids-for-the