You induce a 60yo male for an aorto-bifemoral bypass with severe leg claudication. He has the expected past history of ischaemic heart disease (STEMI 5 years ago – stents + medical management), diabetes, hypertension, and was a 20-pack year ex-smoker.

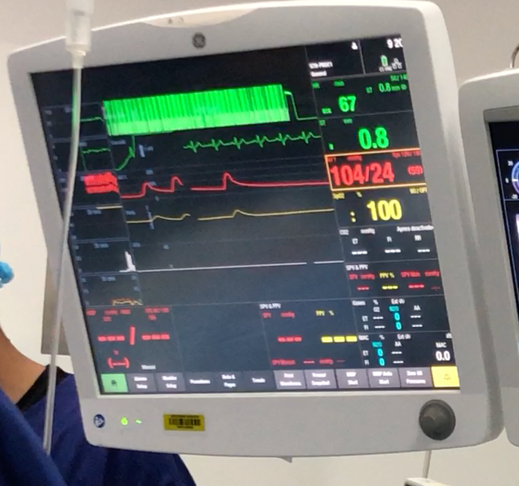

After a reasonably stable induction, his blood pressure continues to need vasopressor. You administer escalating doses of metaraminol, initially a few boluses of 0.5mg followed by an infusion of 5mg/hr, with an unimpressive response for the doses given.

What do you need to consider?

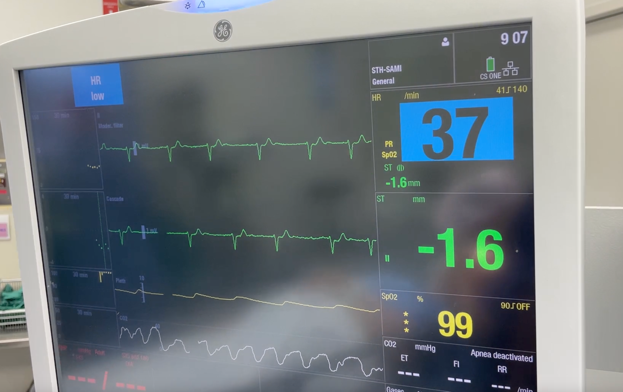

You try to rule out serious causes of hypotension. There’s no significant blood loss, the heart rate and rhythm are normal. There’s no signs of bronchospasm or rash signifying anaphylaxis. There are no ECG changes signifying a pump issue.

What do you do?

In anaesthesia, we are commonly faced with hypotension. The commonest cause of hypotension is simply vasodilation and venodilation caused by hypnotic agents such as propofol or volatile gas. The treatment is easy – fluid and intermittent vasopressor (metaraminol) boluses are the best antidote to this predictable complication.

I find that this expected pattern can also lull us into a false sense of security. We observe and treat hypotension on a daily basis. However, hypotension is also a sign of several catastrophic complications – severe haemorrhage, anaphylaxis, sepsis, cardiogenic causes of shock etc. If we don’t consider and rule out these serious causes, they are likely to cause severe morbidity.

But let’s step back from the serious causes. Sometimes the BP remains low or less responsive to fluid and vasopressor without there being a life-threatening complication.

I find it useful to take a systematic approach and consider PRRCA – preload, rate, rhythm, contractility and afterload. It is completely reasonable to temporise with metaraminol and fluids to treat the common causes (preload and afterload), but it’s critical that we don’t forget to consider contractility, rate and rhythm.

Rate and rhythm are easy to rule out. Look at the ECG and heart rate. Check for sinus rhythm, check if the rate is too slow or fast and treat accordingly.

Contractility is difficult to assess in anaesthesia without echocardiography but I would argue that poor contractility is exactly the cause in many of these cases, especially if the patient is elderly with a history of ischaemic heart disease.

What’s my approach?

If the blood pressure has minimal response after repeated boluses of metaraminol (and I’ve ruled out serious causes and the rate and rhythm are normal), I administer a small dose of a beta agonist (ephedrine 3-6mg). This counteracts the decrease in contractility due to anaesthesia agents on an at-risk patient (vasculopath, IHD, elderly).

This is a simple and safe intervention that avoids unnecessary increases in vasopressor which in turn forces a poorly contractile heart to pump against a higher afterload.

For my complete approach to managing crises, check out this video about the 4 phases of crisis management.

If you have any questions, please write in the comments below!

Dr Lahiru