By Zheng Cheng Zhu

Key reference:

Olesnicky, B. (2023). GLP-1 agonists and gastric emptying. Bulletin. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) & Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM). Winter 2023 edition, p20

Quick Summary

-

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a short-acting, endogenous incretin hormone produced by the gastrointestinal tract to reduce glycaemia by:

-

stimulating beta cell insulin release,

-

delaying gastric emptying, and

-

promoting satiety.

-

-

GLP-1 agonists (~tide, e.g semaglutide) are used as second/third line agents for management of non-insulin dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

-

Owing to their pleiotropic effects, GLP-1 agonists are also approved for management of weight loss, and are increasingly recognised for their cardiometabolic protective effects.

-

However, the risk of aspiration due to delayed gastric emptying has raised concern regarding the safety of GLP-1 agonists in the perioperative setting:

-

The ANZCA Safety and Quality Committee recently presented two case reports of gastric contents identified on elective gastroscopy in patients using GLP-1 agonists despite adequate fasting times.

-

Further research is required to determine the risk-benefit profile of GLP-1 agonists and inform clinicians whether these agents can be safely continued perioperatively.

Preamble

You are an anaesthetic trainee allocated to the elective scope list. You review Ms. OZ, a 56 yo F, BMI 33, awaiting her gastroscopy for her iron-deficiency anaemia. Her PMHx includes type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) for which she takes metformin XR 1g BD, gliclazide 60mg daily, and her recently commenced weekly semaglutide injection. She tells you she has diligently followed your fasting instructions, and didn’t take her morning diabetes med as instructed. Her BSL is 7.5 on arrival.

Gentle propofol sedation proceeds smoothly as your gastroenterology colleague inserts the gastroscope. Suddenly, your colleague exclaims in annoyance

“this patient isn’t fasted!”

You glance over the big screen, and to your disbelief, there are old chunks of the patient’s dinner. You immediately perform a rapid sequence induction to protect the patient’s airway and the gastroenterologist is able to take some biopsies and to a limited scope.

After the procedure Ms. OZ wakes up safely. You disclose to them that because of the food identified on the scope. Ms. OZ is puzzled as to why there was food in her system, given she last ate during dinner last night, to which her husband corroborates.

The above scenario was not dissimilar to recent case reports presented at the latest ANZCA Safety and Quality Committee published in the ANZCA Bulletin, Winter 2023. In the report, two patients on glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists had significant gastric contents during elective gastroscopy despite adequate fasting.

This has significant implications on the risk profile of GLP-1 agonists in the perioperative setting. Whilst there is consensus appreciation of the reduction in perioperative cardiometabolic complications these agents provide in improving glycaemic control, it would be remiss to discount the unquantified risk of aspiration from GLP-1 agonists during airway management.

Presently, the Australian Diabetes Society (ADS) and ANZCA Perioperative Diabetes and Hyperglycaemia Guidelines (November 2022) provide the universal recommendation to withhold all non-insulin antihyperglycaemics on day of surgery, including GLP-1 agonists, with SGLT2 inhibitors to be withheld 2 days prior to surgery. This generalised rule certainly does not address the prolonged therapeutic effects of newer weekly GLP-1 formulations and unknown legacy effects on reduced gastric motility.

Here, we review the physiology and pharmacology of GLP-1 agonists, their current clinical indications, nuanced perioperative considerations, and areas of research needed to establish the safest use of these agents for our patients.

What is GLP-1 and its effect?

GLP-1 is an endogenous incretin peptide hormone produced from intestinal L-cells predominantly located in the terminal ileum. It is produced rapidly in response to nutrient ingestion, and has multiple endocrine and CNS effector sites through GLP-1 receptors which lead to reduced glycaemia. GLP-1 is subsequently rapidly inactivated by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) with a half-life of 1-3 minutes.

In T2DM, there is reduced prandial release of GLP-1 with preserved pancreatic response, making GLP-1 an attractive pathway for antihyperglycaemic agents.

Table 1. Effects of GLP-1 agonism at various effector sites

|

GLP-1 agonist sites |

Effects |

|

Pancreas beta-islet cells |

Stimulates insulin synthesis and release -> increase tissue glucose uptake, promote hepatic and muscle glycogenesis

|

|

Pancreatic alpha cells |

Suppresses glucagon release -> reduce liver gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and glucose release |

|

Gastric neuronal plexus Gastric vagal afferent |

Reduces gastric motility and delays gastric emptying -> promotes satiety, reduces food intake, leading to weight loss |

|

Hypothalamus |

Activates central satiety centers and reduces behavioural food intake -> promotes weight loss |

|

Sino-atrial node |

Increases heart rate

|

Clinical indications of GLP-1 agonists

Like insulin, GLP-1 agonists are hormone mimics restricted to subcutaneous injectables as their only route of administration. The first generation of GLP-1 agonists (e.g. exenatide, lixisenatide) were designed to resist DPP-4 metabolism, and had half-lives of ~3hrs necessitating twice-daily or daily dosing. With second generation GLP-1 agonists (liraglutide, dulaglutide), emphasis turned to increasing protein binding, reducing renal clearance, thus further prolonging drug half-life to now permit weekly injectable formulations (e.g semaglutide).

GLP-1 agonists is currently approved as second/third-line therapy for T2DM patients with inadequate glycaemic control (HbA1c ≥7.0 or ≥53 mmol/mol) despite lifestyle modifications and first-line antihyperglycaemics (metformin/sulfonylurea/insulin).

Liraglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 agonist, is also approved as adjunct pharmacotherapy with lifestyle modification for weight management, particularly for patients with BMI ≥27 kg/m2, with or without T2DM.

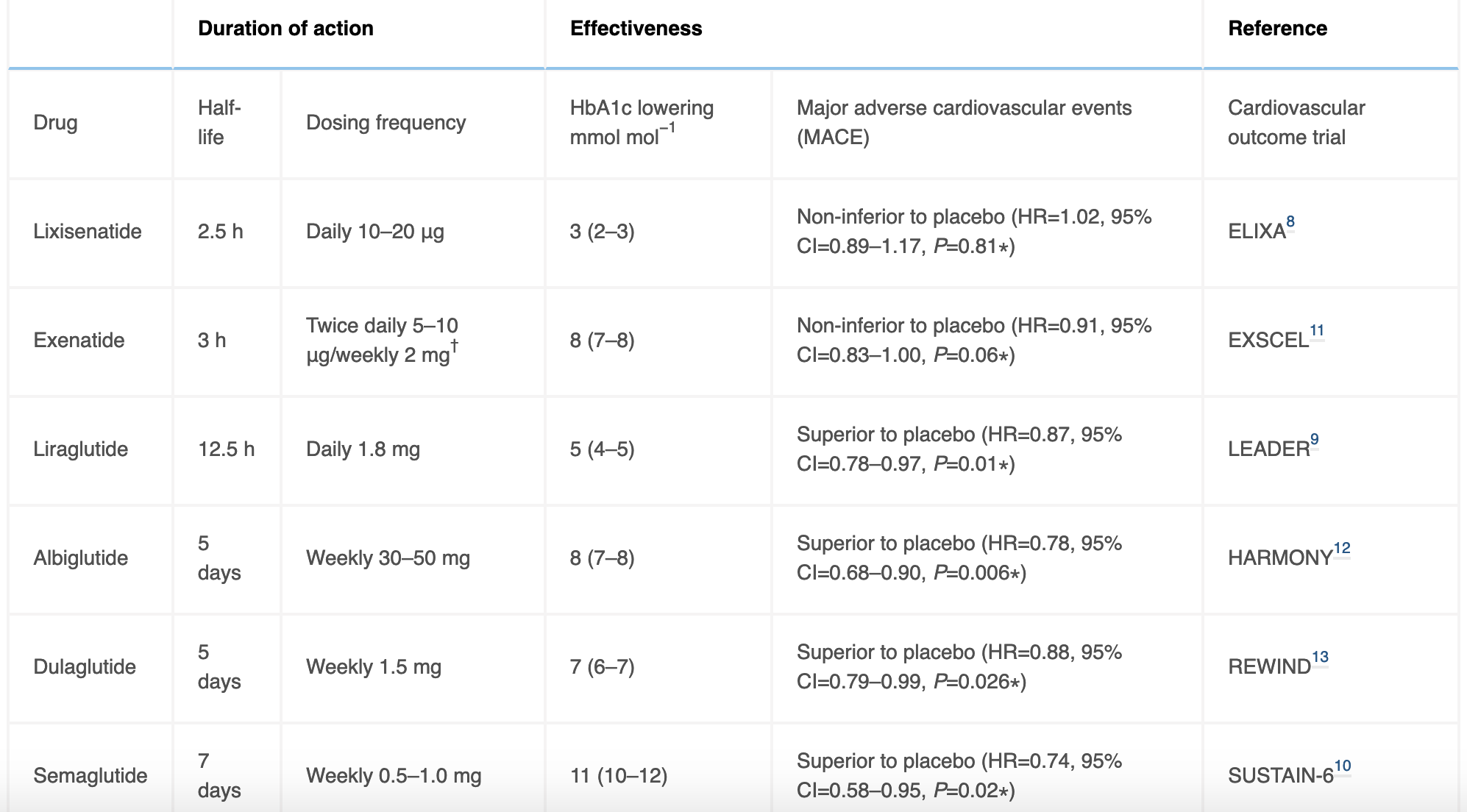

In addition to established efficacy for glycaemic control and weight loss, there has been growing enthusiasm surrounding the cardioprotective effects of GLP-1 agonists, as demonstrated from their superiority to placebo in multiple large studies in preventing major cardiovascular adverse events, namely reduced rates of myocardial infarcts, stroke, and rates of revascularisation procedures (Table 2). Whilst exact mechanisms remain unclear, a combination of risk factor reduction in improved HbA1c, weight, metabolic profile, as well as direct effects of GLP-1 agonism on coronary endothelial function and improved microvascular perfusion is likely at play.

Table 2. Overview of currently available GLP-1 agonists, detailing dose half-life, HbA1c lower effects, and outcomes of major cardiovascular safety trials.

Perioperative considerations

With their superiority in glycaemic control, low incidence of fasting hypoglycaemia, roles in weight management, and established evidence for their cardiovascular benefits, GLP-1 agonists present as highly attractive agents in improving patient outcomes in the perioperative setting, with growing interest for these agents to be continued without perioperative interruption.

Indeed, several recent studies using perioperative GLP-1 agonists have demonstrated improved glycaemic control and reduced insulin requirements in cardiac and non-cardiac surgeries without increase in hypoglycaemia or other adverse events.

However, anaesthetists must take into account the theoretical increased risk of aspiration in patients taking GLP-1 agonists, as presented by the aforementioned case reports. The effects of delayed gastric emptying may further compound the risk factors harbored by the obese, diabetic patient:

-

Gastroparesis secondary to diabetes-related autonomic dysfunction

-

Bowel dysmotility from opioids (chronic pain) and prolonged bed-rest

-

Altered oesophageal-gastric anatomy from bariatric surgery

-

Gastric insufflation from overzealous bag-valve ventilation with high PEEP and difficult airway

-

Reduced efficacy of routine antiemetic regime

Nausea and vomiting are reported by approximately 50% of patients using GLP-1 agonists, as direct results of reduced gastric motility and activation of central satiety centers. However, these effects are often mild, and appear to dissipate over time with continuous use, with patients treated with liraglutide returning to near-baseline gastric emptying by week 8 of therapy.

Moreover, in patients with established gastroparesis, such as those with long-standing diabetes or critical illness, GLP-1 agonists did not significantly worsen gastric motility. Existing literature has also failed to establish an association between GLP-1 agonist and increased postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Nevertheless, concerning case reports and retrospective studies have emerged in 2023 of undigested gastric contents in sedated/anaesthetised patients undergoing elective endoscopy with unprotected airways:

-

Klein and Hobai (2023) published a case report of a patient taking semaglutide for weight loss who experienced pulmonary aspiration from undigested food content identified during routine gastroscopy, despite fasting 18hr prior to the procedure.

-

Kobori and colleagues (2023) identified through their case-control study significantly higher gastric residues on gastroduodenoscopy in diabetic patients treated with GLP-1 agonists than paired controls.

-

Silveira and colleagues (2023) highlighted in a retrospective chart review semaglutide-treated patients were 5 times more likely to have residual gastric content on elective esophagogastroduodenoscopies than non-semaglutide-treated patients.

Risk-benefit implications

With increasing prevalence of GLP-1 agonists in our perioperative population and emerging reports of retained gastric content despite recommended fasting guidelines, a review on the perioperative handling of GLP-1 agonists and assessment of these patients are warranted to balance their cardiometabolic benefits and unquantified risk of catastrophic pulmonary aspiration.

Considering the prolonged half-life of most GLP-1 agonists currently prescribed, it is unfeasible to withhold these agents for weeks prior to surgery to achieve normalisation of gastric function with unknown impact on aspiration rates, appreciating the detrimental effects of poorer glycaemic control on withholding these agents and associated higher risk of peri/postoperative complications (major cardiovascular events, poor wound healing, increased wound infection etc.).

With paucity of high-quality data informing practice, anaesthetists must employ higher vigilance towards patients using GLP-1 agonists, acknowledging the already elevated risks these patients have for complex airways. Use of gastric ultrasound may be prudent for high-risk patients presenting with symptoms of indigestion or nausea/vomiting, however its utility in high-turnover, low resource settings is limited. Further research into the optimal management of GLP-1 agonists in the perioperative period is therefore needed.

References

Australian Diabetes Society and Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. ADS-ANZCA Perioperative Diabetes and Hyperglycaemia Guidelines Adults (November 2022)

Beam, W. Guevara, L. (2023). Are Serious Anesthesia Risks of Semaglutide and Other GLP-1 Agonists Under-Recognized? Case Reports of Retained Solid Gastric Contents in Patients Undergoing Anesthesia. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. June 8, 2023. Accessed on 31 Aug 2023. URL: https://www.apsf.org/article/are-serious-anesthesia-risks-of-semaglutide-and-other-glp-1-agonists-under-recognized/

Hulst, A. H., Polderman, J. A. W., Siegelaar, S. E., van Raalte, D. H., DeVries, J. H., Preckel, B., & Hermanides, J. (2021). Preoperative considerations of new long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetes mellitus. British journal of anaesthesia, 126(3), 567–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.10.023

Klein, S. R., & Hobai, I. A. (2023). Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report. Sémaglutide, vidange gastrique retardée et aspiration pulmonaire peropératoire : une présentation de cas. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d’anesthesie, 10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3

Kobori, T., Onishi, Y., Yoshida, Y., Tahara, T., Kikuchi, T., Kubota, T., Iwamoto, M., Sawada, T., Kobayashi, R., Fujiwara, H., & Kasuga, M. (2023). Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment with gastric residue in an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Journal of diabetes investigation, 14(6), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.14005

Olesnicky, B. (2023). GLP-1 agonists and gastric emptying. Bulletin. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) & Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM). Winter 2023 edition, p20

Silveira SQ, da Silva LM, de Campos Vieira Abib A, de Moura DTH, de Moura EGH, Santos LB, Ho AM, Nersessian RSF, Lima FLM, Silva MV, Mizubuti GB. Relationship between perioperative semaglutide use and residual gastric content: A retrospective analysis of patients undergoing elective upper endoscopy. J Clin Anesth. 2023 Aug;87:111091. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111091. Epub 2023 Mar 2. PMID: 36870274.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Management of type 2 diabetes: A handbook for general practice. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2020.