By Toby Thomas, Zheng Cheng Zhu

Purpose of the pre-anaesthetic assessment:

- Identify patients who have increased peri-operative risk;

- Diagnose, assess, and optimise patient comorbidities to minimise peri-operative risk;

- Plan and prepare for the patient’s perioperative journey;

- Encourage patient-centred discussion regarding risk and benefit of surgery and to reach a decision on whether to proceed or delay/cancel.

The structure and depth of the preoperative anaesthesia assessment will vary depending on the severity and stability of the patient, the urgency (elective versus emergency) and risk profile (low risk vs high risk) of the surgery. However, a general structure is always required to encapsulate the key domains imperative for perioperative planning. There is no fixed method, and juniors are encouraged to observe different styles used by perioperative clinicians and adopt one’s own. Here we present the key areas that should be explored during a pre-operative assessment:

- Detailed History

- Anaesthetic history

- Past medical history, with specific focus on cardiovascular and respiratory systems

- Medication history

- Social history & functional status

- Targeted examination

- Airway assessment

- Vital signs

- CVS exam

- Respiratory exam

- Relevant investigations

- Surgical considerations

- Risk stratification

Detailed History

- Anaesthetic history

- Any issues with prior anaesthetics. Any difficulties encountered with regional/neuroaxial anaesthesia.

- Family history of GA issues -> malignant hyperthermia (MH), sux apnoea (SA) due to pseudocholinesterase deficiency.

- Previous difficult airway.

- Anaphylaxis & other adverse drug reactions.

- Any unplanned HDU/ICU admission following anaesthetic?

The best predictor of intraoperative anaesthetic complications is previous complications and patterns.

Reviewing the previous anaesthesia chart can be a wealth of information. Aside from reviewing major complications and airway grade, note induction medications and doses, vasopressor, analgesics, and antiemetic use. For example, a patient with stable looking blood pressure recordings but needing large doses of metaraminol and ephedrine would be a red flag for any future inductions. Was this a mild case of anaphylaxis, or a sign of decreased cardiac function and undiagnosed heart failure?

Patients with previous anaesthetic issues such as difficult airway, anaphylaxis, MH or SA often carry letters or have electronic record prompts to alert clinicians. Any family members who have undergone genetic or allergy testing after an anaesthetic should prompt the clinician to chase further correspondences of the nature, indications and results of the investigations.

Any unplanned admission to an intensive care setting post-operatively should be reviewed, particularly if the admission was anaesthesia-related:

- Airway trauma / oedema preventing safe extubation.

- Refractory bronchospasm / aspiration event / unexplained oxygenation & ventilation defects requiring ongoing invasive positive pressure ventilation (IPPV).

- Delayed emergence requiring prolonged airway/respiratory support.

- Intraoperative haemodynamic compromise / cardiac event.

- Intraoperative neurologic event.

Etc.

-

Past medical history (PMHx)

With the advancement of perioperative medicine and minimally invasive interventions, clinicians are faced with growing numbers of multimorbid patients who are considered for surgery. This requires a succinct structure to identify and review pertinent PMHx that is relevant for the perioperative setting. Of the body systems, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions are the biggest contributors to perioperative morbidity and mortality.

With any condition that is identified, the following acronym developed by Dr. Lahiru Amaratunge can be used to elucidate important details of the condition:

SSCCT

Severity: how severe is the condition

Stability: is there any acute change recently

Cause: why has this condition occurred

Complications: has this condition led to other disease

Treatment: what is the management, is it working, what is the follow-up

Based on this, one can quickly determine the level of attention you need to pay for a particular condition.

For example, an asthmatic with 2 previous ICU admissions requiring IPPV, with an FEV1/FVC of 0.5, who has presented with new wheeze and cough, on the background of newly diagnosed pulmonary hypertension despite regular preventers and biologics, presents far greater perioperative risks than another mild but otherwise fit asthmatic who barely uses salbutamol PRN with no previous hospital admissions.

Cardiovascular disease:

-Enquire about: chest pain, syncope, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, leg swelling, syncope

-Cardiac comorbidities:

-

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)/ ischaemic heart disease

-

Cardiac arrhythmias

-

Congestive heart failure (CCF)

-

Valvular disease, in particular aortic stenosis (AS) / mitral stenosis (MS)

-

Pulmonary hypertension (pulmHTN)

-

Congenital heart disease

-Current management, such as coronary stenting and/or bypass, AICD/pacemaker

-Patient exercise tolerance, using validated scoring systems. E.g. Duke activity status index (DASI), metabolic equivalent tasks (MET)

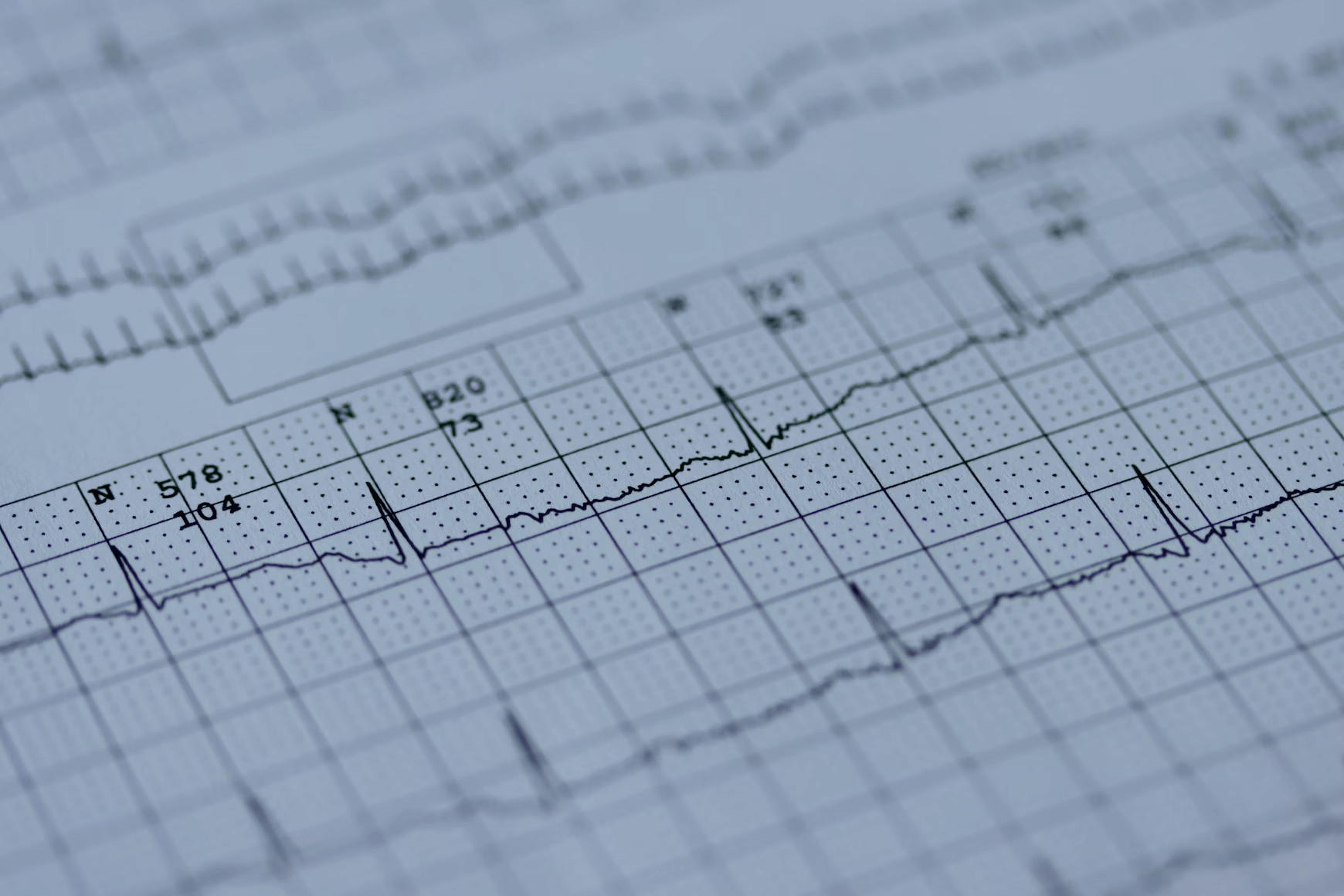

-Recent cardiac investigations: ECG/Holter/TTE/stress TTE/CT cardiac/angiogram

Respiratory disease:

-Enquire about: exertional tolerance, requirement for home oxygen, hospitalisations in the past 12 months due to respiratory illness, current or former smoker?

-Recent respiratory function tests

-Illnesses of note: COPD, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, OSA

-Consider the STOP-BANG questionnaire to detect undiagnosed OSA (see below)

Other:

-Diabetes: T1 vs T2? Insulin dependent? Recent HbA1c? Recent hypo/hyperglycaemic episodes?

-Thyroid, renal, liver disease

–GORD, conditions affecting lower oesophageal sphincter function and/or delayed gastric emptying (poorly controlled reflux poses increased intra operative aspiration risk and may affect induction technique)

-Fasting status, GLP-1 agonist use?

-Conditions which may affect the cervical spine e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis

-In women of reproductive age, ask about possibility of pregnancy

-

Patient medications

-Medications of note include

-

Anticoagulants, antiplatelets

-

Cardiac, including ACEi/ARB, beta blockers

-

Diabetes medications (in particular insulin, SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists) [Check ANZCA’s latest guidelines https://www.anzca.edu.au/safety-and-advocacy/standards-of-practice/clinical-practice-recommendations-regarding-patients-taking-glp-1],

-

DMARDs, steroids and other immunosuppressive medications

-

Opioids and other long-acting opioid replacement therapies

-Consider the need for peri operative anticoagulation bridging for patients on warfarin

-Patient allergies – clarify type of reaction e.g. anaphylaxis vs medication side effect )

-

Social History & functional status

–Smoking and alcohol intake

-Other illicit drug use

-Activities of daily living, whether patient is requiring assistance with basic or complex tasks, fatigue and overall frailty

Examination

The physical exam should include a thorough airway, cardiovascular and respiratory assessment, but may include other systems depending on the patient.

Airway assessment

-Modified Mallampati score

-Thyromental distance (note if less than 6cm from thyroid notch to chin when head is extended)

-Inter-incisor distance (should be able to fit approximately 3 fingers when mouth is fully opened)

-Dentition

-Patient body habitus

-Facial hair

-Freedom of neck movements

-Jaw protrusion

The best predictor of a difficult airway is a history of a difficult airway. Recent anaesthetic charts should therefore be reviewed for previous airway grades, ease of BMV, and size of well-seated supraglottic airways.

The above are useful to identify patients with potentially difficult airways, but none in isolation provide the sensitivity nor specificity to confirm one. Nevertheless, the greater the presence of difficult airway risk factors, the more preparation is required in our airway planning. Importantly, if a genuine difficult airway is anticipated, such as those with fixed flexion deformity, extremely limited mouth opening, or retrognathia with limited jaw protrusion, an awake fibreoptic technique should be discussed with the patient and the anaesthetic team looking after the patient.

Cardiovascular

–Key vitals: BP, HR

-Chest auscultation, noting any cardiac murmurs or added heart sounds, bilateral added lung sounds

–Fluid status, noting any pedal oedema

Respiratory

-SpO2, RR, work of breathing, presence of adventitious breath sounds

Investigations

Further investigations depend on the individual patient’s comorbidities, type of surgery and time available for optimisation before their operation

Young patients undergoing low risk elective surgery may not require any investigations prior to surgery.

Bloods:

- FBE (anaemia or thrombocytopenia, or if having major surgery)

- EUC (eGFR, electrolytes, creatinine)

- LFT (if known or suspected liver disease e.g. Hepatitis)

- HbA1c (elective surgery will often be postponed for patients with poorly controlled HbA1c e.g. > 9)

- TSH (known or suspected thyroid illness)

- Coagulation profile (if patient takes anticoagulant medications (particularly warfarin) or haematological disease/ high bleeding risk)

- Group and hold +- crossmatch (if blood loss anticipated)

Bedside:

- ECG (particularly for older patients, those with cardiovascular disease or those having high risk surgery)

- Pregnancy test: for women of reproductive age

Imaging:

- TTE (may be considered on basis of ECG, unexplained dyspnoea, or if known or suspected CCF or valvular disease, see below)

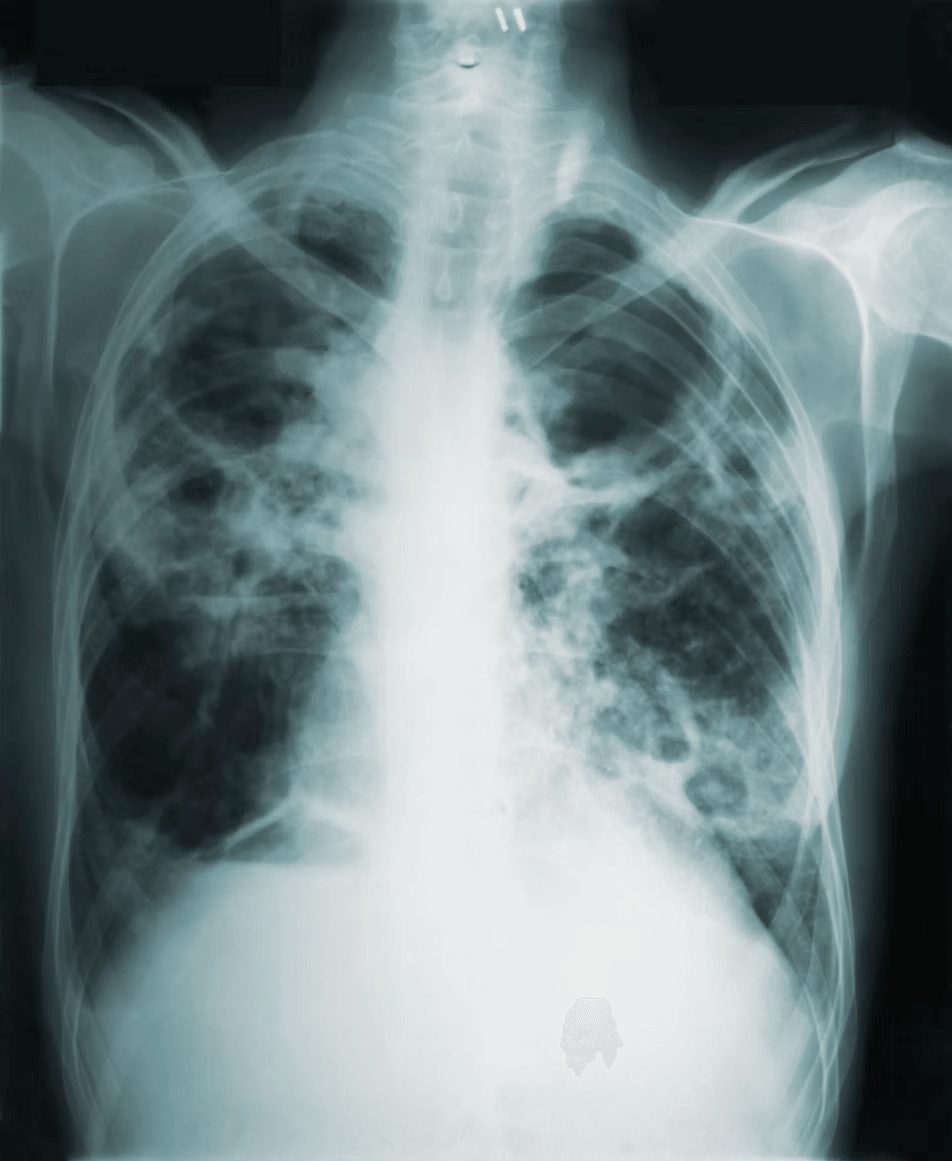

- CXR (not routine but may be done if suspected cardiovascular/pulmonary disease)

Other:

- Respiratory Function Tests: to quantify airways disease (COPD/ asthma/ ILD) or if underlying respiratory illness suspected

- Cardiac stress test: may be considered for patients with cardiovascular disease (see below)

- Dental clearance: if concerns on airway assessment (false teeth, poor dentition etc)

Surgical Considerations

Many surgeries present their own unique challenges that anaesthetists must prepare for in our perioperative planning. As junior trainees build up their volume of practice and gain experience in the specific considerations of particular surgeries, it is often helpful to discuss with our surgical colleagues to better understand their special requirements. As always, a general structure helps to encapsulate broad surgical factors that should be included in our planning:

Space: Patient and Surgery

- How is the patient positioned? Supine, lithotomy, lateral, prone, Tredelenburg?

- Each position is associated with cardiovascular, respiratory changes and specific pressure injury risks.

- How is the patient oriented? Head away from anaesthetic machine? Is our airway close to operative site?

- These will present logistical challenges that need to be navigated on the day.

- Do I have access to my IV?

- This is absolutely imperative in cases where access will be restricted, such as when arms are fully tucked or during robotic cases. Make sure you are confident with your IV, and have at least two if total intravenous anaesthesia is used.

- Where and how big is the operative site?

- Certain regional techniques are extremely useful as a sole method of providing anaesthesia or as an adjunct to perioperative analgesia, especially in high-risk multimorbid patients or in patients where opioid minimisation is ideal. Knowing where the incisions are will help determine the best block technique.

Time: Duration and special timepoints

- How long is the surgery?

- Duration of surgery often correlates with the complexity, degree of physiological insult, and risk of perioperative complications, such as MACE, hypothermia, major fluid shift, delayed emergence, post-operative nausea & vomiting etc.

- Are there critical moments that require special attention? Some examples include:

- Laparoscopic surgery: pneumoperitoneum

- Limb surgery: tourniquet tightening & release

- Major vascular: vessel clamping & release

- Neurosurgery: head pin, aneurysm clamping

Bleeding

Major cardiac, hepatic, vascular, obstetric and orthopaedic surgeries often carry significant bleeding risk, and appropriate perioperative management should be in place:

- Preoperative:

- Up-to-date group and hold, with option for 2x crossmatched blood ready

- Management of anaemia through combination of iron supplementation, optimisation of comorbidities, and blood loss minimisation (withholding of antiplatelet/anticoagulants)

- Intraoperative:

- 2x large bore IV, hot fluid line, rapid infuser device, cell saver, blood available, ROTEM/TEG available

Special cases

- Nerve monitoring e.g. thyroidectomy, plastics reconstruction, nerve repair

- Intraoperative avoidance of neuromuscular blockers to ensure nerve can be monitored

Risk stratification:

There are several tools which are very useful in assessing patient anaesthetic/ surgical risk. These can be used to make decisions about pre-operative optimisation and predict care requirements in the post operative period.

American Society of Anaesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System (ASA):

Useful to assess and communicate a patient’s medical comorbidities.

ASA 1 – A normal healthy patient – e.g. healthy non smoking patient

ASA 2 – A patient with mild systemic disease – e.g. current smoker, obesity, pregnancy

ASA 3 – A patient with severe systemic disease – e.g. poorly controlled diabetes, hypertension

ASA 4 – A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life – e.g. MI or stroke < 3 months ago

ASA 5 – Moribund patient, not expected to survive the next 24 hours, with or without surgery – e.g. ruptured aortic aneurysm

ASA 6 – Declared brain dead, entering theatre for organ retrieval purposes

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) represent one of the most significant complications contributing to perioperative morbidity and mortality. The presence of major cardiovascular conditions, such as ACS, CCF and arrhythmias, as well as any new, acute-on-chronic, or untreated conditions, all disproportionally increase the risk of MACE. Clinicians must consider the benefit-risk profile of delaying surgery for optimisation of these conditions.

The 2024 AAHA/ACC Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Non-cardiac Surgery provides a detailed flowchart to assist clinicians in deciding the most appropriate actions for patients presenting with significant cardiac comorbidities for non-cardiac surgery. To summarise:

Table 1. Adaptation of Figure 1 of 2024 AAHA/ACC Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Non-cardiac Surgery

-

-

-

-

- Is it emergency surgery

If YES -> Proceed with surgery If NO -> Move to step 2

- Does patient have either

- ACS (within 60 days)

- Unstable arrhythmias

- Decompensated CCF

If YES -> consider postponing surgery for management of acute cardiac condition - If ACS is managed with drug-eluding stent (DES) PCI requiring cessation of 1 or more antiplatelet therapy

- Delay for 12 months

- Delay for 3 months for time sensitive surgery

Also consider if any new or undiagnosed/untreated cardiac conditions

If NO -> Move to step 3

- Does the patient have

- Elevated risk for MACE based on validated risk calculators and/or

- Have any risk modifiers?

Validated risk scores include:

- Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)

- American College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator (ACS-SRC)

Risk modifiers are:

- Severe valvular heart disease

- Severe pulmHTN

- Elevated risk congenital heart disease

- Prior coronary stent/coronary bypass

- Recent stroke

- AICD or pacemaker

- Frailty

If Low risk score AND no modifiers -> Proceed with surgery - Represents low risk procedure / low clinical risk

If elevated risk score but no modifiers:

- Consider ECG for asymptomatic patients with no established CVD

- Commence or optimise guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT)

Once complete, move to step 4

If any risk modifier present:

- TTE for evaluation of left ventricular function, valvular pathology, or new symptoms

- Commence and optimise guideline-directed medical therapy

And

- For valvular pathology, consideration of corrective intervention (valve repair/replacement)

Once complete, move to step 4

- Does the patient have reduced or unknown functional capacity, MET <4 or DASI <32

If NO -> Proceed to surgery If YES -> move to step 5

- Will further testing change management

If NO* -> Proceed to surgery OR consider non-operative options If YES -> move to step 6

- Does patient have elevated risk based on cardiac biomarkers:

- NT-proBNP / BNP

- Troponin

If NO -> Proceed to surgery If YES:

- Consider TTE or stress testing, and follow-up with

- Low risk findings -> Proceed

- Elevated risk -> GDMT and consideration of non-operative options

- Proceed w/ post-op cardiac biomarker surveillance

-

-

-

The 2024 AHA/ACC guideline provides a structured framework that can be adapted for any medical condition that may pose increased perioperative risk to patients. A useful mnemonic by Dr. Lahiru Amaratunge distils the steps of the 2024 AHA/ACC guideline that can be universally applied:

“Every Anaesthetist Loves Morning Coffee”

- Emergency surgery -> proceed, with as much optimisation as possible;

- Active condition -> if new condition or acute decompensation/deterioration, consider postponing;

- Low risk -> if low risk procedure / low clinical risk -> proceed

- MET >4 -> proceed

- Cardiac investigations (or investigations relevant for the condition) -> further risk stratification and optimisation

Conclusion:

The preoperative anaesthesia assessment aims to minimise a patient’s intra and post operative risk. It encompasses a focused history, examination and select investigations. The assessment is influenced by the patient’s comorbidities, the risk of the operation, and the urgency of the operation.

Useful links:

Peri operative medication management – UpToDate

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/perioperative-medication-management

STOP-BANG Questionnaire

https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3992/stop-bang-score-obstructive-sleep-apnea

Mallampati Score – LITFL

https://litfl.com/mallampati-score/

NSQIP Risk Calculator Tool

https://riskcalculator.facs.org/RiskCalculator/index.jsp

DASI – MDCalc

https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3910/duke-activity-status-index-dasi#evidence

References:

Ng ACC, Kritharides L. Preoperative assessment: a cardiologist’s perspective. Aust Prescr 2014;37:188-91.https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2014.079

Pang, C. L., Gooneratne, M., & Partridge, J. S. L. (2021). Preoperative assessment of the older patient. BJA education, 21(8), 314-320.

Lamperti, M., Romero, C. S., Guarracino, F., Cammarota, G., Vetrugno, L., Tufegdzic, B., … & Afshari, A. (2025). Preoperative assessment of adults undergoing elective noncardiac surgery: Updated guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. European Journal of Anaesthesiology| EJA, 42(1), 1-35.

Hendrix, J. M., & Garmon, E. H. (2025). American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Writing Committee Members, Thompson, A., Fleischmann, K. E., Smilowitz, N. R., de Las Fuentes, L., Mukherjee, D., Aggarwal, N. R., Ahmad, F. S., Allen, R. B., Altin, S. E., Auerbach, A., Berger, J. S., Chow, B., Dakik, H. A., Eisenstein, E. L., Gerhard-Herman, M., Ghadimi, K., Kachulis, B., Leclerc, J., Lee, C. S., … Williams, K. A., Sr (2024). 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Noncardiac Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 84(19), 1869–1969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.06.013