By Victor Li

Key reference:

Savic, L., Stannard, N. and Farooque, S. (2020). Allergy and anaesthesia: managing the risk. BJA Education, 20(9), pp.298–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.04.005.

Key Takeaways

- Anaesthetists have an important role in identifying and reducing the risk of allergic reactions in the peri-operative period

- Careful history-taking and appropriate investigations during pre-operative assessment can greatly reduce risk of anaphylaxis and improve patient safety

- Consideration of the relative risk of allergy of individual drugs and early recognition of signs of anaphylaxis will greatly improve patient outcomes

- In the event of an allergic reaction, careful documentation of the event, anaesthetic charts, mast cell tryptase, and collaboration with allergy specialists will guide future anaesthesia

Preamble

You are a medical student on your anaesthetics rotation, where you meet Ms Sue Doenim, a 35-year-old female with a body mass index of 34kg/m2 who has presented for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. She has had a previous tonsillectomy at the age of 12 and reported developing a rash due to antibiotics given to her post-operatively. She also reports a latex allergy. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. Induction goes smoothly, when all of a sudden, your supervising anaesthetist asks you:

“How can we minimise the risk of anaphylaxis for Ms Doenim?”

What is the rash that Ms Doenim is referring to?

Perioperative hypersensitivity reactions refer to adverse events ranging from minor to life-threatening, which occur in relation to a surgical procedure. Although the causative mechanism may be allergic or non-allergic, the clinical presentation of a hypersensitivity reaction is indistinguishable regardless of the underlying cause1.

The Ring and Messmer Classification System is a four-step scale, and the most widely accepted tool used to grade hypersensitivity reactions (Table 1)2. Grade 1 and 2 reactions are generally not life-threatening, whereas Grade 3 and 4 reactions are life-threatening, also called ‘anaphylaxis’.

|

Grade |

Summary |

Specific signs and symptoms |

|

Grade 1 |

Generalised mucocutaneous signs |

Erythema Urticaria Angioedema |

|

Grade 2 |

Multi-organ manifestations |

Mucocutaneous signs Bronchospasm, dyspnoea Hypotension, tachycardia Nausea, abdominal cramps |

|

Grade 3 |

Severe life-threatening multi-organ manifestations |

Arrythmia, tachy/bradycardias Cardiovascular collapse Bronchospasm Vomiting, defecation Cutaneous signs |

|

Grade 4 |

Cardiopulmonary arrest |

Cardiac arrest |

The United Kingdom Royal College of Anaesthetists’ 6th National Audit Project estimates the incidence of severe life-threatening anaphylaxis to be 1 in roughly every 10,000 anaesthetic procedures3. However, limitations due to incomplete data may have led to an underestimate of the true incidence by up to 70%, and substantial geographical variability exists on top of that3. Despite optimal clinical care, hypersensitivity reactions, and especially perioperative anaphylaxis, is still associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

- More than 50% of patients require admission to critical care, 70% of whom require Level 3 care3

- Mortality estimates are approximately 4%3

- 1/3 of patients experience significant physical or psychological harm3

Incidence of less severe grades of reaction are poorly defined and likely to be further under-reported. Furthermore, these mild hypersensitivity reactions can be easily missed during surgery for a multitude of reasons:

- Familiar mucocutaneous signs such as urticaria and erythema may be obscured by surgical drapes

- Symptoms such as itch, dyspnoea, angioedema and abdominal pain cannot be reported by the anaesthetised patient

- Bronchospasm may be masked by invasive ventilation

- Alterations in heart rate and blood pressure such as hypotension and tachycardia occur commonly and may be interpreted as normal physiological responses during surgery especially during induction of anaesthesia

- Hypotension is common with a dose of propofol

- Tachycardia is a common sympathetic response to the pain of laryngoscopy and surgical incision.

How can we minimise the risk of hypersensitivity reactions preoperatively?

Patients who have either had a history of unexplained or un-investigated perioperative hypersensitivity reactions and meet the criteria for referral to anaesthetic allergy clinic should be investigated before further surgery, given that surgery is not urgent4. Formal testing in an allergy clinic to identify the causative agent of anaphylaxis not only guides future anaesthetic decisions, but also avoids attributing the anaphylaxis to the wrong causal drug, which would expose the patient to the risk of both re-exposure to the real culprit drug, and unnecessary avoidance of non-causal, potentially important drugs. Once the allergy is confirmed or excluded, clinicians can proceed with routine anaesthesia, however if allergy is suspected or no information is available, surgery should be postponed to allow for referral to allergic services and further investigations.

Other strategies anaesthetists can employ in pre-operative assessment to minimise risk intra-operatively include taking a history of previous chlorhexidine exposure and avoiding incorrect labelling of patients with untested penicillin allergy. There is increasing recognition of the negative outcomes associated with penicillin allergy labels including a 50% increase in surgical site infections, increased length of hospital stay and increased mortality5,6. Thus, correcting untested penicillin allergy labels is not only important for antimicrobial stewardship, but also avoids unnecessarily withholding important antibiotics, ultimately achieving better patient outcomes6.

In the case that the patient must undergo urgent or emergency surgery, clinicians should gather relevant patient history and anaesthetic charts to determine if allergy or anaphylaxis is suspected and identify potential causative agents. If previous anaesthetic charts are unavailable and there is high suspicion for hypersensitivity reactions, the anaesthetist may have to proceed in a manner that minimises risk of perioperative anaphylaxis7. This may include:

- Avoiding all drugs used in the previous anaesthetic course (if previous charts available)

- Using as few drugs as possible

- Using anaesthetic drugs with the lowest risk of allergy

- Using regional or inhalational techniques if possible

- Avoiding neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) if possible

- Avoiding chlorhexidine and latex if possible

- Avoiding penicillins and cephalosporins if antibiotics are indicated

- Consulting local anaesthesia allergy services for advice and input

What measures can we take during anaesthesia and surgery to minimise the risk of hypersensitivity reactions?

Regardless of the history or risk of anaphylaxis in a patient, some strategies that anaesthetists may consider in all surgeries to minimise risk may include:

- Preventing accidental re-exposure (especially chlorhexidine due to unclear labelling and ubiquitous inclusion in cleaning products)

- Consider whether all drugs administered are strictly indicated

- Careful monitoring for signs of anaphylaxis

- Specific consideration for drugs with known allergy risk8 – NMBAs (suxamethonium, atracurium, rocuronium), reversal agents (sugammadex), colloids and antibiotics (beta-lactams, teicoplanin)

- Prophylactic antihistamines may alleviate mild symptoms, e.g. itch in the hours following anaphylaxis, but have no role in the prevention of allergic reactions7

- Current evidence does not support the use of antibiotic test doses, however, it may be useful to administer the antibiotic 5-10 mins before induction, in order to be certain of the cause of the allergic reaction1.

- In NAP 6, anaphylaxis presented in 83% of cases in first 10mins10. In less than 2% of cases, the presenting feature was delayed more than 60 minutes.

How do we manage a suspected anaphylaxis?

Immediate management as per 2022 consensus guidelines from the International Suspected Perioperative Allergic Reactions group (ISPAR) include9:

- Withdrawal of the offending agent if known

- Call for help early

- Maintain anaesthesia with minimal anaesthetic agent until situation is stabilised. Balance the risk between level of hypnotic/amnestic and worsening hypotension. A modified EEG monitor may aid in this situation.

- Place patient in Trendelenburg position or leg raising manoeuvres

- Airway support with 100% O2, and optimise ventilation for bronchsopasm

- Volume resuscitation with continuous IV fluids until haemodynamically stable. 1-2 litres may be needed rapidly in severe cases.

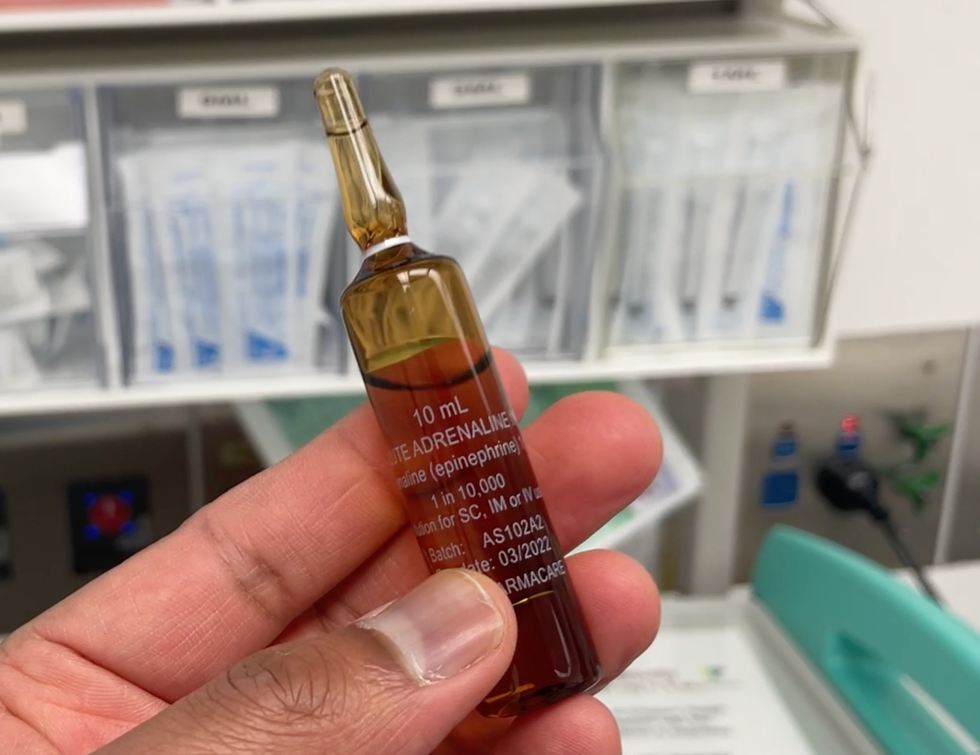

- IV adrenaline titrated to effect with close monitoring of cardiovascular responses (Table 2)9

|

Severity of allergic response |

Adrenaline dosage |

|

Grade 1 |

No adrenaline required |

|

Grade 2 |

10-20mcg IV adrenaline. Escalate to 50mcg if insufficient response to initial dose. Consider initial 500 microgram IM adrenaline as a safe and effective alternative in adults. |

|

Grade 3 |

50-100mcg IV adrenaline. Escalate to 200mcg if insufficient response to initial dose. |

|

Grade 4 |

1000mcg IV adrenaline immediately in PEA arrest and then repeated every 1-2 minutes. Follow ALS guidelines for shockable rhythms |

A key decision must also be made as to whether to continue or abandon surgery, and if continuing, what drug choices need to be made. This decision should be made clinically by the anaesthetist and surgical teams, guided by the degree of surgical urgency and stability of the patient1. When proceeding, some key considerations include:

- discontinuing all potential culprit drugs where possible (any drug given IV within 1 hour of the reaction occurring, any gels, bone cements, medical dyes, or cleaning solutions)

- keeping surgery chlorhexidine- and latex-free (e.g. using chlorhexidine-free boxes which contain alternatives)

- utilising NMBAs from a different class if an NMBA was used before the reaction and further doses are needed

Mast cell tryptase (MCT) sampling is gold standard for diagnosis of anaphylaxis, as increases in MCT indicates widespread mast cell degranulation has occurred1. A peak MCT level should be taken as soon as possible once the patient is stable or within the first 4 hours of the event, and a baseline sample should be taken at least 24 hours after the event1. A significant increase is defined by the peak MCT level being greater than (1.2 x baseline MCT) + 2 ng/ml, although anaphylaxis also cannot be excluded when there is no MCT increase.

All patients who have suffered a suspected perioperative allergic reaction should be referred to a specialist allergy clinic for targeted investigations, no matter the grade of reaction. This referral should be made by the anaesthetist and must include a copy of the anaesthetic chart with details of all drugs and compound exposures. Common perioperative allergens like chlorhexidine, latex, medical dyes, gels and sprays may not be tested for if not documented1. The referral process can be made easier with the help of ‘Suspected Anaphylaxis Follow-Up Packs’, available on the NAP6 resources page of the Association of Anaesthetists Website4,10.

References

- Savic, L., Stannard, N. and Farooque, S. (2020). Allergy and anaesthesia: managing the risk. BJA Education, 20(9), pp.298–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.04.005.

- Kroigaard M, Garvey LH, Gillberg L, Johansson SG, Mosbech H, Florvaag E, et al. Scandinavian clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis, management and follow‐up of anaphylaxis during anaesthesia*. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2007;51(6):655–70. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01313.x

- Harper NJN, Cook TM, Garcez T, Farmer L, Floss K, Marinho S, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: Epidemiology and clinical features of perioperative anaphylaxis in the 6th national audit project (NAP6). British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018;121(1):159–71. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.014

- Harper NJN, Cook TM, Garcez T, Lucas DN, Thomas M, Kemp H, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: Management and outcomes in the 6th national audit project (NAP6). British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018 Jul;121(1):172–88. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.015

- Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;133(3):790–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

- West R, Smith C, Pavitt S, Butler C, Howard P, Bates C, et al. “warning: Allergic to penicillin”: Association between penicillin allergy status in 2.3 million NHS General Practice Electronic Health Records, antibiotic prescribing and health outcomes [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2019 [cited 2024 Jan 7]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31225607/

- Garvey LH, Dewachter P, Hepner DL, Mertes PM, Voltolini S, Clarke R, et al. Management of suspected immediate perioperative allergic reactions: An international overview and consensus recommendations. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019 Jul;123(1). doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.04.044

- Mertes PM, Ebo DG, Garcez T, Rose M, Sabato V, Takazawa T, et al. Comparative epidemiology of suspected perioperative hypersensitivity reactions. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019 Jul;123(1). doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.027

- Pedersen K, Roessler P, Tran R. Perioperative anaphylaxis management guideline background paper – ANZAAG [Internet]. ANZCA FPM; 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 7]. Available from: https://media.anzaag.com/2022/11/22130754/Anaphylaxis-Mx-Guideline-BP-Nov2022.pdf

- Anaphylaxis and Allergies NAP6 Resources [Internet]. The Association of Anaesthetists; 2024 [cited 2024 Jan 7]. Available from: https://anaesthetists.org/Home/Resources-publications/Safety-alerts/Anaesthesia-emergencies/Anaphylaxis-and-allergies